INTRODUCTION.

THE chronicles of the ancient Kings of Persia, who extended their empire into the Indies, and as far as China, tell of a powerful king of that family, who dying, left two sons. The eldest, Shahriar, inherited the bulk of his empire; the younger, Shahzenan, who like his brother Shahriar was a virtuous prince, well beloved by his subjects, became King of Samarcande.

After they had been separated ten years, Shahriar resolved to send his vizier to his brother to invite him to his court. Setting out with a retinue answerable to his dignity, that officer made all possible haste to Samarcande. Shahzenan received the ambassador with the greatest demonstrations of joy. The vizier then gave him an account of his embassy. Shahzenan answered thus:—“Sage vizier, the Sultan does me too much honour; I long as passionately to see him, as he does to see me. My kingdom is in peace, and I desire no more than ten days to get myself ready to go with you; there is no necessity that you should enter the city for so short a time: I pray you to pitch your tents here, and I will order provisions in abundance for yourself and your company.”

At the end of ten days, the King took his leave of his Queen, and went out of town in the evening with his retinue, pitched his royal pavilion near the vizier’s tent, and discoursed with that ambassador till midnight. But willing once more to embrace the Queen, whom he loved entirely, he returned alone to his palace, and went straight to her apartment.

The King entered without any noise, and pleased himself to think how he should surprise his wife, whose affection for him he never doubted. Great was his surprise, when by the lights in the royal chamber, he saw a male slave in the Queen’s apartment! He could scarcely believe his own eyes. “How!” said he to himself, “I am scarce gone from Samarcande, and they dare thus disgrace me!” And he drew his scimitar, and killed them both; and quitting the town privately, set forth on his journey.

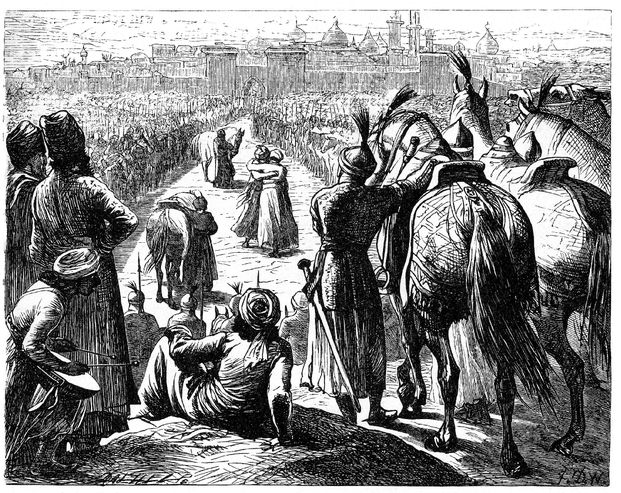

When he drew near the capital of the Indies, the Sultan Shahriar and all the court came out to meet him: the princes, overjoyed at meeting, embraced, and entered the city together, amid the acclamations of the people; and the Sultan conducted his brother to the palace he had provided for him.

But the remembrance of his wife’s disloyalty made such an impression upon the countenance of Shahzenan, that the Sultan could not but notice it. Shahriar endeavoured to divert his brother every day, by new schemes of pleasure, and the most splendid entertainments; but all his efforts only increased the King’s sorrow.

One day, Shahriar had started on a great hunting match, about two days’ journey from his capital; but Shahzenan, pleading ill health, was left behind. He shut himself up in his apartment, and sat down at a window that looked into the garden.

The meeting of the brothers.

Suddenly a secret gate of the palace opened, and there came out of it twenty women, in the midst of whom walked the Sultaness. The persons who accompanied the Sultaness threw off their veils and long robes, and Shahzenan was greatly surprised when he saw that ten of them were black slaves, each of whom chose a female companion. The Sultaness clapped her hands, and called: “Masoud, Masoud!” and immediately a black came running to her; and they all remained conversing familiarly together.

When Shahzenan saw this he cried: “How little reason had I, to think that no one was so unfortunate as myself!”—So, from that moment he forbore to repine. He ate and drank, and he continued in very good humour; and when the Sultan returned, he went to meet him with a shining countenance.

Shahriar was overjoyed to see his brother so cheerful; and spoke thus: “Dear brother, ever since you came to my court I have seen you afflicted with a deep melancholy; but now you are in the highest spirits. Pray tell me why you were so melancholy, and why you are now cheerful?”

Upon this, the King of Tartary continued for some time as if he had been meditating, and contriving what he should answer; but at last replied as follows: “You are my Sultan and master; but excuse me, I beseech you, from answering your question.”—“No, dear brother,” said the Sultan, “you must answer me; I will take no denial.” Shahzenan for a time hesitated to reply; but not being able to withstand his brother’s importunity, told him the story of the Queen of Samarcande’s treachery: “This,” said he, “was the cause of my grief; judge, whether I had not reason enough to give myself up to it.”

Then Shahriar said: “I cease now to wonder at your melancholy. But, bless Allah, who has comforted you; let me know what your comfort is, and conceal nothing from me.” Obliged again to yield to the Sultan’s pressing instances, Shahzenan gave him the particulars of all that he had seen from his window. Then Shahriar spoke thus: “I must see this with my own eyes; the matter is so important, that I must be satisfied of it myself.” “Dear brother,” answered Shahzenan, “that you may without much difficulty. Appoint another hunting match; and after our departure you and I will return alone to my apartments; the next day you will see what I saw.” The Sultan, approving the stratagem, immediately appointed a new hunting match; and that same day the tents were set up at the place appointed.

Next day the two princes set out, and stayed for some time at the place of encampment. They then returned in disguise to the city, and went to Shahzenan’s apartment. They had scarce placed themselves in the window, when the secret gate opened, the Sultaness and her ladies entered the garden with the blacks. Again she called Masoud; and the Sultan saw that his brother had spoken truth.

“O heavens!” cried he, “what an indignity! Alas! my brother, let us abandon our dominions and go into foreign countries, where we may lead an obscure life, and conceal our misfortune.” “Dear brother,” replied Shahzenan, “I am ready to follow; but promise me that you will return when we meet any one more unhappy than ourselves.” So they secretly left the place. They travelled as long as it was day, and passed the first night under some trees. Next morning they went on till they came to a fair meadow on the sea-shore, and sat down under a large tree to refresh themselves.

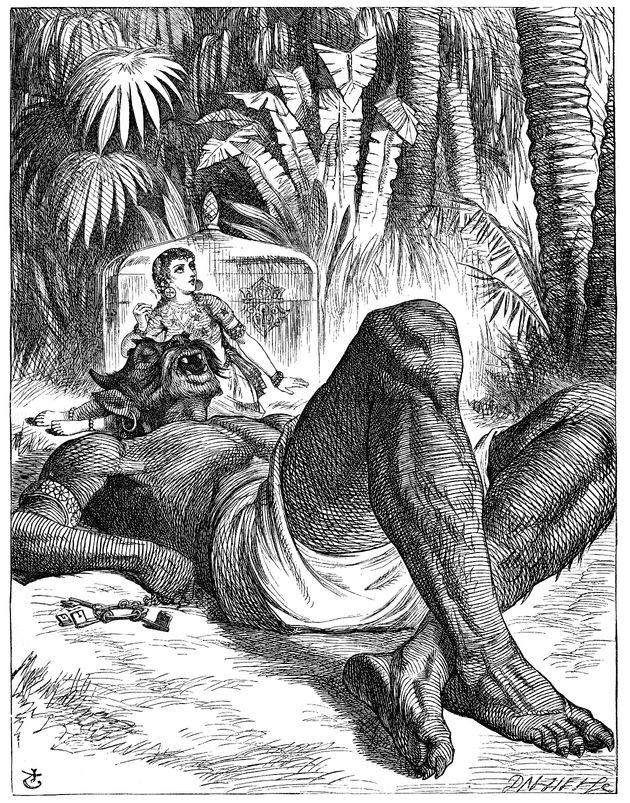

Soon they heard a terrible noise; the sea opened, and there arose out of it a great black column, ascending towards the clouds. Then they were seized with fear, and climbed up into the tree to hide themselves. And the dark column advanced towards the shore, and there came forth from it a black genie, of prodigious stature, who carried on his head a great glass box, shut with four locks of fine steel. He came into the meadow and laid down his burden at the foot of the tree in which the two princes were hidden. The genie opened the box with four keys that he had at his girdle, and there came out a lady magnificently apparelled, and of great beauty. Then the genie said: “O lady, whom I carried off on your wedding day, let me sleep a few moments.” Having spoken thus, he laid his head upon her knee and fell asleep.

The lady looking up at the tree, saw the two princes, and made a sign to them to come down without making any noise. But they were afraid of the genie, and would fain have been excused. Upon this she laid the monster’s head softly on the ground, and ordered them to come down, saying, “If you hesitate, I will wake up this genie, and he shall kill you.” So the princes came down to her. And when she had remained with them for some time, she pulled out a string of rings, of all sorts, which she showed them, and said: “These are the rings of all the men with whom I have conversed, as with you. There are full fourscore and eighteen of them, and I ask yours to make up the hundred. This wicked genie never leaves me. But he may lock me up in this glass box, and hide me in the bottom of the sea: I find a way to cheat his care. You may see by this, that when a woman has formed a project, no one can hinder her from putting it into execution.” Then said the two kings: “This monster is more unfortunate than we.” So they returned to the camp, and thence to the city.

The sleeping genie and the lady.

Then Shahriar ordered that the Sultaness should be strangled; and he beheaded all her women with his own hand. After this he resolved to marry a virgin every day, and to have her killed the next morning. And thus every day a maiden was married, and every day a wife was sacrificed.

The report of this unexampled cruelty spread consternation through the city. And at length, the people who had once loaded their monarch with praise and blessings, raised one universal outcry against him.

The grand vizier, who was the unwilling agent of this horrid injustice, had two daughters, the eldest called Scheherazade, and the youngest Dinarzade. The latter was a lady of very great merit; but the elder had courage, wit, and penetration in a remarkable degree. She studied much, and had such a tenacious memory, that she never forgot any thing she had once read. She had successfully applied herself to philosophy, physic, history, and the liberal arts; and made verses that surpassed those of the best poets of her time. Besides this, she was a perfect beauty; all her great qualifications were crowned by solid virtue; and the vizier passionately loved a daughter so worthy of his affection.

One day, as they were discoursing together, she said to him, “Father, I have one favour to beg of you, and most humbly pray you to grant it me.”—“I will not refuse it,” he answered, “provided it be just and reasonable.”—“I have a design,” resumed she, “to stop the course of that barbarity which the Sultan exercises upon the families of this city.”—“Your design, daughter,” replied the vizier, “is very commendable; but how do you intend to effect it?”—“Father,” said Scheherazade, “since by your means the Sultan celebrates a new marriage, I conjure you to procure me the honour of being his bride.”

This proposal filled the vizier with horror. “O heavens,” replied he, “have you lost your senses, daughter, that you make such a dangerous request to me? You know the Sultan has sworn by his soul that he will never be married for two days to the same woman; and would you have me propose you to him?”—“Dear father,” said the daughter, “I know the risk I run; but that does not frighten me. If I perish, at least my death will be glorious; and if I succeed, I shall do my country an important piece of service.”—“No, no,” said the vizier, “whatever you can represent to induce me to let you throw yourself into that horrible danger, do not think that I will agree to it. When the Sultan shall order me to strike my dagger into your heart, alas! I must obey him; what a horrible office for a father!”—“Once more, father,” said Scheherazade, grant me the favour I beg.”—“Your stubbornness”—replied the vizier—“will make me angry; why will you run headlong to your ruin? I am afraid the same thing will happen to you that happened to the ass, who was well off, and could not keep so.”

“Father,” replied Scheherazade, “I beg you will not take it ill that I persist in my opinion.” In short, the father, overcome by the resolution of his daughter, yielded to her importunity; and though he was very much grieved that he could not divert her from her fatal resolution, he went that minute to inform the Sultan that next night he would bring him Scheherazade.

The Sultan was much surprised at the sacrifice which the grand vizier proposed making. “How could you resolve,” said he, “to bring me your own daughter?”—“Sir,” answered the vizier, “it is her own offer.” “But do not deceive yourself, vizier,” said the Sultan: “to-morrow when I put Scheherazade into your hands, I expect you will take away her life; and if you fail, I swear that you shall die.”

Scheherazade now set about preparing to appear before the Sultan: but before she went, she took her sister Dinarzade apart, and said to her, “My dear sister, I have need of your help in a matter of very great importance, and must pray you not to deny it me. As soon as I come to the Sultan, I will beg him to allow you to be in the bride-chamber, that I may enjoy your company for the last time. If I obtain this favour, as I hope to do, remember to awaken me to-morrow an hour before day, and to address me in words like these: ‘My sister, if you be not asleep, I pray you that, till day-break, you will relate one of the delightful stories of which you have read so many.’ Immediately I will begin to tell you one; and I hope, by this means, to deliver the city from the consternation it is in.” Dinarzade answered that she would fulfil her sister’s wishes.

When the hour for retiring came, the grand vizier conducted Scheherazade to the palace, and took his leave. As soon as the Sultan was left alone with her, he ordered her to uncover her face, and found it so beautiful, that he was charmed with her; but, perceiving her to be in tears, he asked her the reason. “Sir,” answered Scheherazade, “I have a sister who loves me tenderly, and whom I love; and I could wish that she might be allowed to pass the night in this chamber, that I might see her, and bid her farewell. Will you be pleased to grant me the comfort of giving her this last testimony of my affection?” Shahriar having consented, Dinarzade was sent for, and came with all diligence. The Sultan passed the night with Scheherazade upon an elevated couch, and Dinarzade slept on a mattress prepared for her near the foot of the bed.

An hour before day, Dinarzade awoke, and failed not to speak as her sister had ordered her.

Scheherazade, instead of answering her sister, asked leave of the Sultan to grant Dinarzade’s request. Shahriar consented. And, desiring her sister to attend, and addressing herself to the Sultan, Scheherazade began as follows:—