THE HISTORY OF SINDBAD THE SAILOR.

IN the reign of the same caliph, Haroun Alraschid, whom I mentioned in my last story, there lived in Baghdad a poor porter, who was named Hindbad. One day, during the most violent heat of summer, he was carrying a heavy load from one extremity of the city to the other. Much fatigued by the length of the way he had already come, and with much ground yet to traverse, he arrived in a street where the pavement was sprinkled with rose-water, and a grateful coolness refreshed the air. Delighted with this mild and pleasant situation, he placed his load on the ground, and took his station near a large mansion. The delicious scent of aloes and frankincense which issued from the windows, and, mixing with the fragrance of the rose-water, perfumed the air; the sound of a charming concert issuing from within the house accompanied by the melody of the nightingales, and other birds peculiar to the climate of Baghdad; all this, added to the smell of different sorts of viands, led Hindbad to suppose that some grand feast was in progress here. He wished to know to whom this house belonged; for, not having frequent occasion to pass that way, he was unacquainted with the names of the inhabitants. To satisfy his curiosity, therefore, he appoached some magnificently-dressed servants who were standing at the door, and inquired who was the master of that mansion. ‘What,’ replied the servant, ‘are you an inhabitant of Baghdad, and do not know that this is the residence of Sindbad the sailor, that famous voyager who has roamed over all the seas under the sun?’ The porter, who had heard of the immense riches of Sindbad, could not help comparing the situation of this man, whose lot appeared so enviable, with his own deplorable position; and distressed by the reflection, he raised his eyes to heaven, and exclaimed in a loud voice, ‘Almighty Creator of all things, deign to consider the difference that there is between Sindbad and myself. I suffer daily a thousand ills, and have the greatest difficulty in supplying my wretched family with bad barley bread, whilst the fortunate Sindbad lavishes his riches in profusion, and enjoys every pleasure. What has he done to obtain so happy a destiny, or what crime has been mine to merit a fate so rigorous?’ As he said this he struck the ground with his foot, like a man entirely abandoned to despair. He was still musing on his fate, when a servant came towards him from the house, and taking hold of his arm, said, ‘Come, follow me; my master Sindbad wishes to speak with you.’

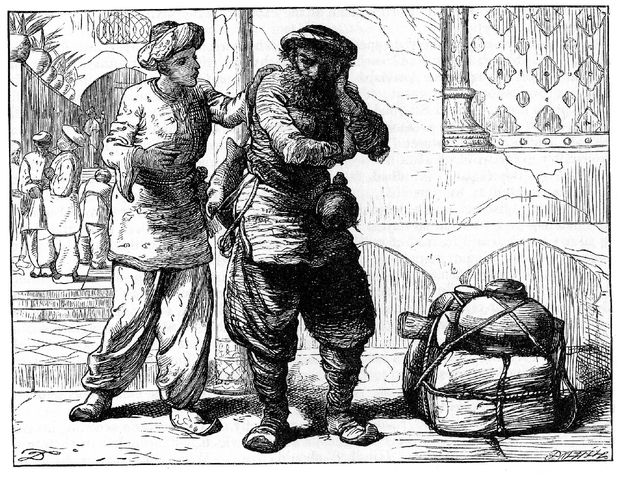

“Hindbad was not a little surprised at the compliment thus paid him. Remembering the words he had just uttered, he began to fear that Sindbad sent for him to reprimand him, and therefore he tried to excuse himself from going. He declared that he could not leave his load in the middle of the street. But the servant assured him that it should be taken care of, and pressed him so much to go that the porter could no longer refuse.

The servant invites Hindbad to the house.

“His conductor led him into a spacious room, where a number of persons were seated round a table, which was covered with all kinds of delicate viands. In the principal seat sat a grave and venerable personage, whose long white beard hung down to his breast; and behind him stood a crowd of officers and servants ready to wait on him. This person was Sindbad. Quite confused by the number of the company and the magnificence of the entertainment, the porter made his obeisance with fear and trembling. Sindbad desired him to approach, and seating him at his right hand, helped him himself to the choicest dishes, and made him drink some of the excellent wine with which the sideboard was plentifully supplied.

“Towards the end of the the repast, Sindbad, who perceived that his guests had done eating, began to speak; and addressing Hindbad by the title ‘my brother,’ the common salutation amongst the Arabians when they converse familiarly, he inquired the name and profession of his guest. ‘Sir,’ replied the porter, ‘my name is Hindbad.’ ‘I am happy to see you,’ said Sindbad, ‘and can answer for the pleasure the rest of the company also feel at your presence; but I wish to know from your own lips what it was you said just now in the street:’ for Sindbad, before he went to dinner, had heard from the window every word of Hindbad’s ejaculation, which was the reason of his sending for him. At this request, Hindbad, full of confusion, hung down his head, and replied, ‘Sir, I must confess to you that, put out of humour by weariness and exhaustion, I uttered some indiscreet words, which I entreat you to pardon.’ ‘Oh,’ resumed Sindbad, ‘do not imagine that I am so unjust as to have any resentment on that account. I feel for your situation, and instead of reproaching you, I pity you heartily; but I must undeceive you on one point respecting my own history, in which you seem to be in error. You appear to suppose that the riches and comforts I enjoy have been obtained without any labour or trouble. In this you are mistaken. Before attaining my present position, I have endured for many years the greatest mental and bodily sufferings that you can possibly conceive. Yes, gentlemen,’ continued the venerable host, addressing himself to the whole company, ‘I assure you that my sufferings have been so acute that they might deprive the greatest miser of his love of riches. Perhaps you have heard only a confused account of my adventures in the seven voyages I have made on different seas; and as an opportunity now offers, I will, with your leave, relate the dangers I have encountered; and I think the story will not be uninteresting to you.’

“As Sindbad was going to relate his history chiefly on the porter’s account, he gave orders, before he began it, to have his guest’s burden, which had been left in the street, brought in, and placed where Hindbad should wish. When this matter had been adjusted, he spoke in these words:—