THE SLEEPER AWAKENED.

DURING the reign of the caliph Haroun Alraschid, there lived at Baghdad a very rich merchant, whose wife was far advanced in years. They had an only son, called Abou Hassan, who had been in every respect brought up with great strictness.

“The merchant died when this son was thirty years old; and Abou Hassan, who was his sole heir, took possession of the vast wealth which his father had amassed, by great parsimony and a constant industry in business. The son, whose views and inclinations were very different from those of his father, very soon began to dissipate his fortune. As his father had not allowed him in his youth more than was barely sufficient for his maintenance, and as Abou Hassan had always envied young men of his own age who had been more liberally supplied, and who never denied themselves any of those pleasures in which young men too readily indulge, he determined in his turn to distinguish himself by making an appearance consistent with the great wealth with which fortune had favoured him. Accordingly, he divided his fortune into two parts. With the one he purchased estates in the country and houses in the city, and, although these would produce a revenue sufficient to enable him to live at his ease, he resolved to let the sums arising from them accumulate; the other half, which consisted of a considerable sum of ready money, was to be spent in enjoyment, to compensate him for the time he thought he had lost under the severe restraint in which he had been kept during his father’s lifetime: but he laid it down as a primary rule, which he determined inviolably to keep, not to expand more than this sum in the jovial life he proposed to lead.

“Abou Hassan soon brought together a company of young men, nearly of his own age and rank in life; and he thought only how he should make their time pass agreeably. To accomplish this he was not content with entertaining them day and night, and giving the most splendid feasts, at which the most delicious viands, and wines of the most exquisite flavour were served in abundance; he added music to all this, engaging the best singers of both sexes. His young friends, on their part, while they indulged in the pleasures of the table, often joined their voices to those of the musicians, and, accompanied by soft instruments, formed a concert of delightful harmony. These feasts were generally followed by balls, to which the best dancers in the city of Baghdad were invited. All these amusements, which were daily varied by new pleasures, were so extremely expensive to Abou Hassan, that he could not continue his profuse style of living beyond one year. The large sum of money which he had devoted to this prodigality ended with the year. So soon as he ceased giving these entertainments his friends disappeared; he never even met them in any place he frequented. In short, they shunned him whenever they saw him; and if by accident he encountered any one of them, and wished to detain him in conversation, the false friend excused himself under various pretences.

“Abou Hassan was more distressed at the strange conduct of his friends, who abandoned him with so much faithlessness and ingratitude after all the vows and protestations of friendship they had made him, than at the loss of all the money he had so foolishly expended on them. Melancholy and thoughtful, with his head sunk upon his breast, and a countenance full of bitter emotion, he entered his mother’s apartment and seated himself at the end of a sofa at some distance from her.

“ ‘What is the matter, my son?’ asked his mother, when she saw him in this desponding state. ‘Why are you so moody, so cast down, and so different from your former self? Had you lost everything you possessed in the world you could not appear more miserable. I know at what an enormous outlay you have lived; and ever since you engaged in that course of dissipation I thought you would soon have very little money left. Your fortune was at your own disposal, and I did not endeavour to oppose your irregular proceedings, because I knew the prudent precaution you had taken of leaving half of your means untouched; while this half remains I do not see why you should be plunged into this deep melancholy.’ Abou Hassan burst into tears at these words, and in the midst of his grief exclaimed, ‘Oh, my dear mother, I know from woeful experience how insupportable poverty is. Yes, I feel very sensibly that as the setting of the sun deprives us of the splendour of that luminary, so poverty deprives us of every sort of enjoyment. Poverty buries in oblivion all the praises that have been bestowed on us, and all the good that has been said of us, before we fell into its grasp. It reduces us at every step to take measures to avoid observation, and to pass whole nights in shedding the bitterest tears. He who is poor is regarded but as a stranger, even by his relations and his friends. You know, my mother,’ continued Abou Hassan, ‘how liberally I have conducted myself towards my friends for a year past. I have exhausted my means in entertaining them in the most sumptuous manner; and now that I cannot continue to do so, I find myself abandoned by them all. When I say that I have it no longer in my power to entertain them as I have done, I mean that the money I had set apart to be employed for that purpose is entirely exhausted. I thank Heaven for having inspired me with the idea of reserving what I call my income, under the rule and oath I made not to touch it for any foolish dissipation. I will strictly observe this oath, and I have resolved to make a good use of what happily remains; but first I wish to see to what extremity my friends, if indeed I can still call them so, will carry their ingratitude. I will see them all, one after another; and when I represent to them the lengths to which I have gone from my regard to them, I will solicit them to raise amongst themselves a sufficient sum of money in some measure to relieve me in the unhappy situation to which I am reduced by contributing to their amusement. But I mean to take this step, as I have already said, only to see whether I shall find in these friends the least sentiment of gratitude.’

“ ‘My son,’ replied the mother of Abou Hassan, ‘I will not take upon myself to dissuade you from executing your plan; but I can tell you beforehand that your hope is unfounded. Believe me, it is useless to attempt this trial; you will receive no assistance but from the property you have yourself reserved. I plainly see you do not yet know those men who, among people of your description, are commonly styled friends; but you will soon know them: and I pray Heaven it may be in the way I wish—that is, for your good.’ ‘My dear mother,’ cried Abou Hassan, ‘I am convinced of the truth of what you tell me: but it will be a more convincing proof to me of those men’s baseness and want of feeling if I learn it by my own experience. ’

“Abou Hassan set out immediately; and he timed his visits so well that he found all his friends at home. He represented to them the great distress he was in, and besought them to lend him such a sum of money as would be of effectual assistance to him; he even promised to enter into a bond to every one individually to return the sums each should lend him, so soon as his affairs were re-established; but he still avoided letting them know that his distresses were in a great measure arising from them; for he wished to give them every opportunity of displaying their generosity. And he did not forget to hold out to them the hope that he might one day be again in a position to entertain them as he had done.

“Not one of his convivial companions was the least affected by Abou Hassan’s distresses and afflictions, though he represented his embarrassments in the most lively colours, hoping he should persuade his friends to relieve him. He had even the mortification to find that many of them pretended not to know him, and did not even remember ever to have seen him. He returned home, his heart filled with grief and indignation. ‘Alas! my mother,’ cried he, as he entered her apartment, ‘you have told me the truth; instead of friends I have found only perfidious, ungrateful men, unworthy of my friendship. I renounce them for ever, and I promise you I will never see them again.

“Abou Hassan kept firmly to the resolution he had made, and took every prudent precaution to avoid being tempted to break it. He bound himself by an oath never to ask any man who was an inhabitant of Baghdad to eat with him. He then took the strong box which contained the money arising from his rents from the spot where he had laid it by, and put it in the place of the coffers he had just emptied. He resolved to take from it for the expenses of each day a regular sum that should be sufficient to enable him to invite one person to sup with him; and he took a second oath, declaring that the person he entertained should not be an inhabitant of Baghdad, but a stranger who had only tarried in the city one day; and determined that he would send him away the next morning, after giving him only one night’s lodging.

“In carrying out his design Abou Hassan took care every morning to make the necessary provision for this limited hospitality; and towards the close of each day he went and sat at the end of the bridge of Baghdad, and as soon as he saw a stranger, whatever the appearance of the wayfarer, he accosted him with great civility, and invited him to sup and lodge at his house on that, the night of his arrival. He at once informed his guest of the rule he had laid down, and the bounds he had set to his hospitality; and thereupon conducted him to his house.

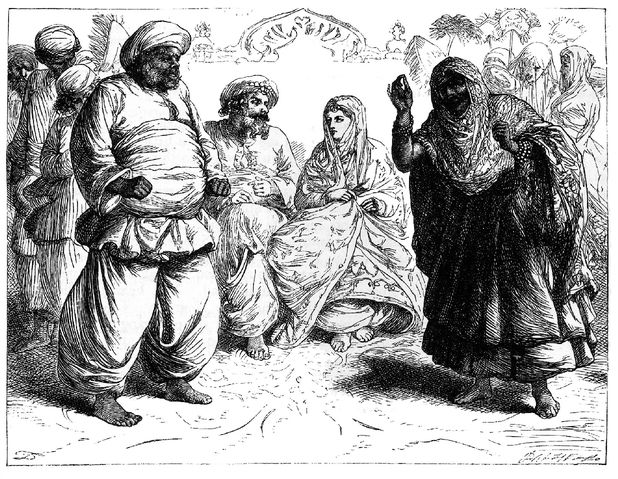

Abou Hassan and the stranger.

“The repast which Abou Hassan set before his guest was not sumptuous; but it was such as might well satisfy a man, especially as there was no want of good wine. They remained at table till almost midnight; and instead of discoursing to his guest, as is customary, on affairs of state, family matters, or business, he used, on the contrary, to talk gaily and agreeably of indifferent things: he was naturally pleasant, good-humoured, and amusing, and whatever the subject was he knew how to give such a turn to his conversation as would enliven the most melancholy of his visitors.

“When he took leave next morning of his guest, Abou Hassan always said: ‘To whatever place you go, may Allah preserve you from every sort of calamity. When I invited you to sup with me yesterday, I informed you of the rule I had laid down for myself: for which reason you must not take it ill if I tell you that we shall never drink together again, nor shall we ever meet each other any more at my house, or any other place. I have my reasons for this course of conduct, which I need not explain to you. May Allah guard you!’

“Abou Hassan observed this rule with great exactness; he never again noticed or addressed the strangers whom he had once received in his house: when he met them in the streets, the squares, or public assemblies, he appeared not to see them, and even turned from them if they accosted him. In short, he avoided the slightest intercourse with them. And for a long time he continued this course of life. But one day, a little before sunset, as he was seated in his usual manner at the end of the bridge, the caliph Haroun Alraschid appeared; but so completely disguised that none of his subjects could know him.

“Although this monarch had ministers and officers of justice, who performed their duty with great exactness, he wished, nevertheless, to look into the working of everything himself. With this design, as we have already seen, he often went in different disguises through the city of Baghdad. He was even accustomed to visit the high environs; and on this account he made it a custom to go on the first day of every month into the high roads which lead to the city, sometimes choosing one road, and sometimes another. That day, the first of the month, he appeared disguised as a merchant from Moussoul, just landed on the other side of the bridge, and was followed by a strong and sturdy slave.

“As the caliph looked in his disguise like a grave and respectable man, Abou Hassan, who believed him to be a merchant from Moussoul, rose from the place on which he was seated. He saluted the stranger with a bland and courteous air, and addressed him thus: ‘O my master, I congratulate you on your happy arrival; I entreat you will do me the honour to sup with me, and pass the night at my house, that you may rest yourself after the fatigue of your journey.’ And to induce the supposed merchant to comply with his request, he told him, in a few words, the rule he had laid down to himself—of every day receiving, for one night only, the first stranger who presented himself.

“The caliph found something so singular in the whimsical taste of Abou Hassan, that he felt an inclination to know something further of him. Therefore, preserving the character of a merchant, he assured Abou Hassan he could not better reply to so great and unexpected a civility, on his arrival at Baghdad, than by accepting the obliging invitation; and accordingly begged his entertainer to lead the way, declaring himself ready to follow him.

“Abou Hassan, who was ignorant of the high rank of the guest whom chance had just presented to him, treated the caliph as if he had been his equal. He took him to his house, showed him into an apartment very neatly furnished, where he seated him on a sofa in the most honourable place. Supper was ready, and the cloth was spread. Abou Hassan’s mother, who was an adept in the culinary art, sent in three dishes. One was a fine capon, garnished with four fat pullets; the other two dishes were a fat goose and a ragout of pigeons. This was the whole provision; but the dishes were well chosen, and excellent of their kind.

“Abou Hassan placed himself at table opposite his guest; and the caliph and he began eating with a good appetite, helping themselves to what they liked best, without speaking and without drinking, according to the custom of their country. When they had done, the slave of the caliph brought them water to wash their hands, while the mother of Abou Hassan took away the dishes, and brought the dessert, which consisted of a variety of the fruits then in season, such as grapes, peaches, apples, pears, and several kinds of cakes made of dried almonds. As the evening closed in they lighted the candles; and then Abou Hassan brought out bottles and glasses, and took care that his mother provided supper for the caliph’s slave.

“When the pretended merchant of Moussoul and Abou Hassan were again seated at table, the latter, before he touched the fruit, took a cup, and filling it for himself, held it out in his hand, ‘O my master,’ said he to the caliph, whom he took to be only a merchant, ‘you know as well as I do that the cock never drinks till he has called his hens about him to come and drink with him; therefore I invite you to follow my example. I know not what your sentiments may be; but, for my own part, it seems to me that a man who hates wine, and would fain be thought wise, is certainly foolish. Let such men deem themselves wise with their stupid and melancholy disposition, but let us enjoy ourselves; I see pleasure sparkling in the cup, and it will assuredly yield much pleasure to those who empty it.’

“While Abou Hassan was drinking, the caliph took hold of the cup that was intended for him, and replied: ‘I agree with you. You are what may be called a jolly fellow. I love you for your humour, and I expect you will fill my cup to the brim as you have filled yours.’

“When Abou Hassan had drunk, he accordingly filled the cup which the caliph held out; ‘Taste it, my friend,’ said he, ‘you will find it excellent. ’ ‘I have no doubt of that,’ returned the caliph, laughing; ‘no doubt a man of discernment like you knows how to procure the best of everything. ’

“While the caliph was drinking, Abou Hassan observed, ‘any man who looks at you may observe at first sight that you are one of those who have seen the world, and know how to enjoy it. If my house,’ added he, quoting some lines of Arabian poetry, ‘were capable of any feeling, and could be alive to the pleasure of receiving you within its walls, it would loudly express its joy, and throwing itself at your feet, would cry out, “Ah! what delight, what happiness is it, to see myself honoured with the presence of a person so respectable, and at the same time so condescending, as the man who now deigns to come under my roof!” In short, my master, my joy is complete, and I count the day fortunate on which I have met with a man of your merit.’

“These sallies of Abou Hassan very much diverted the caliph, who was naturally of a merry disposition, and took pleasure in inducing him to drink, that by means of the gaiety which wine would excite, he might become better acquainted with him. To engage him in conversation he asked him his name, and what was his employment, and how he passed his time. ‘O stranger,’ replied his host, ‘my name is Abou Hassan; I have lost my father, who was a merchant, not indeed a very rich man, but one of those who, at Baghdad, manage to live very much at their ease. At his death he left me an inheritance sufficient to support me creditably in the rank I held. As he had kept me very strictly during his lifetime, and at the time of his death I had passed the best part of my youth under great restraint, I wished to try to make up for all the time I considered I had lost.

“ ‘Nevertheless,’ continued Abou Hassan, ‘I regulated my proceedings with more prudence than is practised by young people in general. They usually give themselves up to intemperance in a very thoughtless way; they indulge in every dissipation till, reduced to their last sequin, they exercise a forced abstinence during the remainder of their life. In order to avoid future distress, I divided my property into two parts; the one consisted of rents, the other of ready money. I devoted the ready money to the enjoyments I purposed indulging in; and made a firm resolution not to touch my rents. I brought together a company of people I knew, men nearly of my own age; and, with the ready money which I freely lavished, I every day gave the most splendid entertainments, living with my friends in luxury which pleased us all well. But this did not last long; at the end of a year I found my purse empty, and at once all my convivial friends disappeared. I made it my business to call upon each of them in turn; I represented to each the wretched state to which I was reduced, but not one of them would give me any assistance. I therefore renounced their friendship; and, reducing my expenses within the limits of my income, I determined that in future I would entertain no one at all, except every day one stranger whom I should meet on his arrival at Baghdad; and I made it a condition that I entertained him for that day only. I have told you the rest, and I thank my good fortune which to day has thrown in my way a stranger of so much merit.’

“Very well, satisfied with this explanation, the caliph said to Abou Hassan, ‘I cannot sufficiently commend the step you took, and the caution with which you acted, when you entered upon your free course of life. You conducted yourself very differently from young men in general; and I respect you still more for keeping your resolution with so much steadiness as you have shown. You walked in a very slippery path; and I cannot sufficiently wonder, after you had spent all your ready money, that you had the moderation to confine yourself within the income arising from your rents; and that you do not mortgage your estate. To tell you what I think of the matter, I firmly believe you are the only man of pleasure that ever did, or ever will, conduct himself in such a manner. In short, I declare that I envy your good fortune. You are the happiest man on earth, thus to have every day the company of a respectable person, with whom you can converse agreeably, and to whom you give an opportunity of telling the world the good reception you have afforded him. But we forget ourselves. Neither you nor I perceive how long we have been talking without drinking; come, drink, and I will pledge you.’ The caliph and Abou Hassan continued drinking a long time, and conversing most agreeably together.

“The night was now far advanced; and the caliph, pretending to be much fatigued with his day’s journey, said to Abou Hassan that he was much inclined to go to rest. ‘I should be loth,’ added he, ‘that, on my account, you should lose any of your sleep. Before we part—for perhaps I shall be gone to-morrow from your house before you are awake—let me have the satisfaction of saying how sensible I am of the civility, the good cheer, and the hospitality with which you have treated me in so obliging a manner. I am only anxious to know in what way I can best prove my gratitude. I entreat you to inform me, and you shall find that I am not an ungrateful man. It is hardly possible that a person like you should not have some business that might be done, some want that should be supplied, some wish that is yet ungratified. Open your heart to me, and speak freely. Though I am but a merchant as you see, I am in a position, either alone, or with the help of my friends, to serve my friends.’

“At these offers of the caliph, whom Abou Hassan all along supposed to be a merchant, he replied, ‘My good friend, I am thoroughly convinced that is not out of mere compliment you address me in this generous manner. But, upon the word of a man of honour, I can assure you that I have no distress, no business, no want; that I have nothing to ask of any one. I have not the smallest degree of ambition, as I have already told you, and am perfectly contented with my lot; so that I have only to thank you, as well for your kind offers as for the kindness you have shown in conferring upon me the honour of taking a poor refreshment at my house.

“ ‘I will say, nevertheless,’ continued Abou Hassan, ‘that one thing gives me some concern, though it does not very materially disturb my repose. You know the city of Baghdad has several divisions, and that in every division there is a mosque. Each mosque has an Iman, who assembles all the people of the division at the accustomed hours to join with him in prayer. The Iman of this division is a very old man, of an austere countenance; he is a complete hypocrite, if ever there was one in the world. He assembles in council four other dotards, my neighbours, very much of the same character with himself, and they meet regularly every day at his house. When they get together there is no sort of slander, calumny, and mischief which they do not raise and propagate against me, and against the whole quarter; they disturb our quiet, and stir up dissen sions among us. They make themselves formidable to some, and threaten others. They wish, in short, to be our masters, and desire that each of us should behave himself according to their caprice, while, at the same time, they cannot govern themselves. To say the truth, I cannot bear to see them busying themselves with everything except the Koran, and it angers me that they cannot let their neighbours live in peace.’

“ ‘So then,’ replied the caliph, ‘you seem desirous of finding means to check this abuse?’ ‘I am, indeed,’ returned Abou Hassan; ‘and the only thing I would beg of Heaven for this purpose is, that I might for one day be caliph in the room of the Commander of the Faithful, our sovereign lord and master, Haroun Alraschid.’ ‘What would you do,’ demanded the caliph, ‘if that should happen?’ ‘One very important thing would I do,’ replied Abou Hassan, ‘which would give satisfaction to all good people. I would order that one hundred strokes on the soles of the feet be given to each of the four old men, and four hundred to the Iman himself, to teach them that it is not their business to disturb and vex their neighbours.’

“The caliph was much amused by the conceit of Abou Hassan; and, as he had naturally a turn for adventures, it suggested to him a desire to divert himself at his host’s expense in a very extraordinary manner. ‘Your wish pleases me the more,’ said the caliph, ‘because I see it springs from an upright heart, and is the sentiment of a person who cannot bear that the malice of wicked men should go unpunished. I should have great pleasure in procuring its fulfilment, and perhaps it is not impossible that what you have imagined may come to pass. I feel certain that the caliph would readily trust his power in your hands for twenty-four hours if he only knew of your good intention, and the excellent use you would make of the opportunity. Although I am but a merchant, and a stranger, I am nevertheless not without a degree of interest which may possibly forward this business.’

Abou Hassan falls asleep.

“ ‘I see plainly,’ replied Abou Hassan, ‘that you are diverting yourself with my foolish fancy—and the caliph would laugh at it also if he came to hear of such a ridiculous whim. Still, it might have the effect of inducing him to inquire into the conduct of the Iman and his counsellors, and order them to be punished.’

“ ‘I am by no means laughing at you,’ replied the caliph; ‘Heaven forbid that I should cherish so unbecoming a thought towards a person like you, who have entertained me so handsomely, though I was quite a stranger to you; and I can assure you the caliph himself would not laugh at you. But let us make an end of this conversation; it is near midnight, and time to go to bed.’

“ ‘Then,’ said Abou Hassan, ‘we will cut short our discourse, and I will not prevent you from taking your repose: but, as there is a little wine still left in the bottle, I pray you let us finish that, and then we will retire. The only thing I have to recommend is, when you leave the house to-morrow morning, if I should not have risen, that you would not leave the door open, but that you would trouble yourself to shut it after you.’ This the caliph faithfully promised to do.

“While Abou Hassan was speaking, the caliph laid hands on the bottle and the two cups. He helped himself first, and made Abou Hassan understand that he drank to him a cup of thanks. When he had done so, he slily threw into Abou Hassan’s cup a little powder, which he had with him, and poured upon it the remainder of the wine from the bottle. Presenting it to Abou Hassan, he said, ‘you have had the trouble of helping me throughout the evening; the least I can do, in return, is to spare you that trouble now at our parting cup: I beg you will take this from my hand, and drink this time for my sake.’

“Abou Hassan took the cup; and the better to prove to his guest with how much pleasure he accepted the honour done him, he swallowed the whole contents at a draught. But scarcely had he set down the cup on the table, when the powder began to take effect. He instantly fell so soundly asleep, and his head dropped almost upon his knees so suddenly, that the caliph could not help laughing. The slave who attended the caliph had returned as soon as he had supped, and had been for some time on the spot, ready to obey his master’s orders. ‘Take this man upon your shoulders,’ said the caliph to him, ‘but be careful to notice the spot where this house stands, that you may bring him back hither when I shall bid you.’

“The caliph, followed by his slave, who bore Abou Hassan on his shoulders, went out of the house; but he did not close the door as Abou Hassan had requested him to do. Indeed, he left it open on purpose. When he arrived at the palace he entered by a private door, and ordered the slave to carry Abou Hassan to his own apartment, where all the officers of the bed-chamber were in waiting. ‘Undress this man,’ said he to them, ‘and lay him in my bed; I will afterwards tell you my intention.’

“The officers undressed Abou Hassan, clothed him in the caliph’s night dress, and put him to bed, as they were ordered. No one in the palace had yet retired to rest. The caliph ordered that all the ladies, and all the other officers of the court should be summoned; and when they were all in his presence, he said; ‘I desire that all those who usually come to me when I rise shall not fail in their attendance here to-morrow morning upon this man, whom you see asleep in my bed; and that upon his waking each shall perform the same services for him which are usually performed for me. I desire also that the same respect be observed towards him that is shown to my own person; and that he be obeyed in all that he shall command. He shall be refused nothing he may demand. All his orders are to be fulfilled, nor is he to be contradicted in any desire he shall express. On every occasion, where it shall be proper to speak to him or to answer him, let him be always treated as the Commander of the Faithful. In one word, I require that no more attention be paid to me by any one all the time you are about him than if he were really what I am, caliph and Commander of the Faithful. Above all, let the utmost care be taken that the deception is carried through, even to the most trifling circumstance. ’

“The officers and ladies, who soon perceived the caliph had some jest in hand, answered only by a low obeisance; and from that moment all of them prepared to contribute everything in their power, each in his or her peculiar function, to support the deception with exactness.

“On his return to the palace the caliph had sent the first officer in waiting to summon the grand vizier Giafar, and the vizier had just arrived. The caliph said to him: ‘Giafar, I sent to you to warn you not to seem astonished when, at the audience to-morrow morning, you shall see the man who is now asleep on my bed seated upon my throne, and dressed in my robes of state. Address him in the same form you employ towards me, and pay him the same respect you are in the habit of paying to me; treat him exactly as if he were the Commander of the Faithful. Wait upon him, and execute punctually all his orders, just as if they were mine. He will most probably make large presents, and you will be entrusted with the distribution of them: fulfil all his commands in this matter, even to the hazard of exhausting my treasury. Remember also to warn my emirs, my ushers, and all the officers not within the palace, that to-morrow at the public audience they shall pay him the same honours they accord to my person, and bid them act their parts so well that he shall be thoroughly deceived, and that the amusement I propose to give myself may not in the smallest particular be broken. You may now retire; I have nothing further to order; but be careful to give me in this matter all the satisfaction which I demand.’

“After the grand vizier had retired, the caliph passed on to another apartment; and as he went to bed he imparted to Mesrour, chief of the eunuchs, the orders which were to be executed, so that everything might succeed in the manner intended; for the caliph wished both to fulfil the wish of Abou Hassan, and to see the use he would make of the royal power and authority during the short time he would possess them. Above all, he enjoined Mesrour not to fail in coming to call him at the usual hour, and before Abou Hassan should be awake, because he wished to be present at all that might take place.

“Mesrour awakened the caliph punctually at the time he was ordered. As soon as Haroun Alraschid had entered the room where Abou Hassan slept, he placed himself in an adjoining closet, whence he could see through a lattice all that took place, without being himself seen. All the officers and all the ladies who were to be present when Abou Hassan rose came in at the same time, and were posted in their accustomed places, according to their rank, and in profound silence, just as if the caliph himself had been about to rise, and they were waiting ready to perform the duties of their various offices.

“As the day already began to break, and it was time to get up for early prayer before sunrise, the officer who was nearest Abou Hassan’s pillow applied to the sleeper’s nose a small piece of sponge dipped in vinegar.

“Abou Hassan sneezed and turned his head, without opening his eyes. Thereupon his head sank back on the pillow. Presently he opened his eyes; and, as far as the dim light permitted him, he saw himself in a large and magnificent chamber, superbly furnished, the ceiling painted with various figures, and elegant borders, and ornamented throughout with vases of massive gold, and with tapestry and carpets of the richest kind. He found himself surrounded by young ladies of enchanting beauty, many of whom had different musical instruments, which they were preparing to play upon; and by black eunuchs richly dressed, and standing ranged in attitudes of deep humility and respect. As he cast his eyes upon the coverlid of the bed, he saw it was of crimson and gold brocade, ornamented with pearls and diamonds; by the bed side lay a dress of the same materials, ornamented in similar style; and near it, on a cushion, a caliph’s cap.

“At the sight of all this splendour Abou Hassan was inexpressibly astonished and bewildered. He looked upon the whole as a dream—but a dream of so charming a nature that he hoped it might prove a reality. ‘Truly,’ said he to himself, ‘it seems I am caliph; but,’ added he, after a pause, on recovering himself, ‘I must not deceive myself, this is a dream, merely an effect of the wish I formed in conversation with my guest—’ so he shut his eyes again as if he intended to go to sleep.

“But at that moment an eunuch drew near. ‘O Commander of the Faithful,’ said he, respectfully, ‘your majesty will be pleased not to sleep again. It is time to rise for early prayer. The day begins to break.’ Abou Hassan, very much astonished at this address, said again to himself, ‘Am I awake, or do I sleep? No, I am certainly asleep—’ continued he, keeping his eyes still closed—‘I must not doubt it.’

“O Commander of the Faithful,’ resumed the eunuch, who observed that Abou Hassan gave no answer, and showed no signs of intending to rouse himself, ‘your majesty will allow me to repeat that it is time to rise, unless your majesty means to disregard the hour of morning prayer, which you are accustomed to attend; and the sun is even now appearing.’

“ ‘I was deceiving myself,’ said Abou Hassan, ‘I am not asleep, I am awake. Those who sleep never hear anything; and I certainly hear that I am spoken to.’ Then he opened his eyes again. It was now daylight, and he saw distinctly what he had before only imperfectly beheld. He sat up in his bed with a cheerful countenance, like a man much rejoicing at finding himself in a situation very far above his rank; and the caliph, who watched him without being himself seen, penetrated his thoughts with great satisfaction.

“Then the beautiful ladies of the palace bowed down before Abou Hassan, with their faces towards the ground; and those among them who had instruments of music saluted him on his awaking with a concert of soft-toned flutes, hautbois, lutes, and various other instruments. This so enchanted him, and raised him to such an excess of delight, that he knew not where he was, and almost lost consciousness. He recurred, nevertheless, to his first thought, and again doubted whether what he saw and heard was a dream or reality. He covered his eyes with his hands, and bending his head repeated to himself, ‘What does all this mean? Where am I? What has happened to me? What is this palace? Whence come these eunuchs, these gallant handsome officers, these beauteous damsels, and these enchanting musicians? Is it possible that I should not be able to distinguish whether I am dreaming, or whether I have all my senses about me!’ At last he took his hands from his face; and opening his eyes to look up, he saw the sun darting its first rays through the window of the chamber in which he lay.

“At this moment Mesrour, the chief of the eunuchs, came in. He bowed down, with his face to the ground, before Abou Hassan, and as he rose said, ‘Commander of the Faithful, your majesty will permit me to represent that you have not been accustomed to rise so late, nor have you ever suffered the hour of morning prayer to pass unregarded. Unless your majesty has had a bad night, or is otherwise indisposed, you will now be pleased to mount your throne, to hold your council, and to give audience as usual. The generals of your armies, the governors of your provinces, and the other great officers of your court, await the moment when the door of the council chamber shall be opened.

“At this address of Mesrour, Abou Hassan was, as it were, convinced against his own judgment that he was not asleep, and that the splendours which he saw around him were not a dream. He was much perplexed; he felt bewildered at the position he was in, and uncertain what part he should take. At length he fixed his eyes upon Mesrour, and, in a serious tone, demanded of him, ‘Whom are you addressing? Who is it that you call Commander of the Faithful? I know you not; you must certainly take me for some other person.’

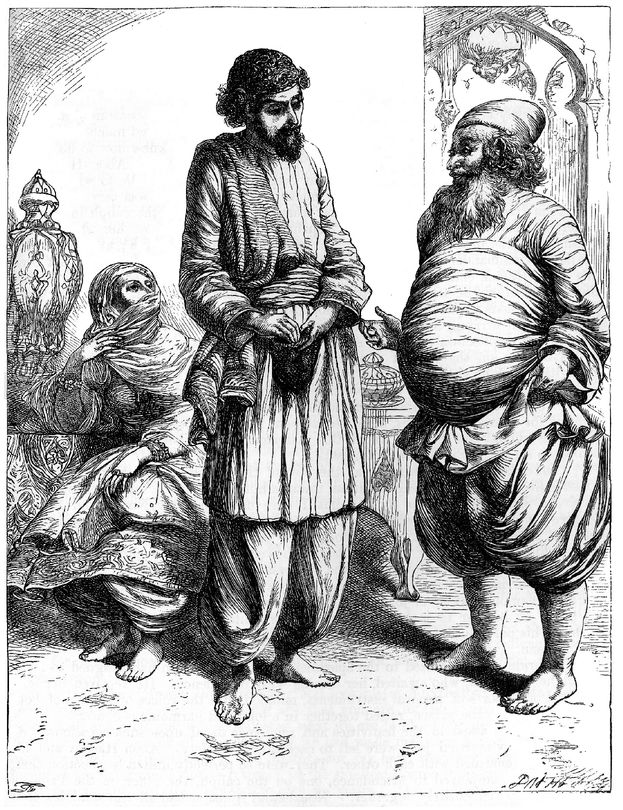

Abou Hassan as caliph.

“Any man but Mesrour would have been disconcerted at Abou Hassan’s questions; but, instructed by the caliph, he played his part wonderfully well. ‘O my most honoured lord and master,’ cried he, ‘your majesty surely talks thus to me to-day in order to try me! Is not your majesty the Commander of the Faithful, the monarch of the world from the east to the west? and upon earth vicar of the prophet sent from Allah, who is master of all, both in Heaven and in earth? Your poor slave Mesrour has not forgotten all this, after the many years during which he has had the honour and happiness of paying his duty and services to your majesty! He would think himself the most miserable of men if he were to lose your good opinion. He most humbly entreats your majesty to have the goodness to restore him to your favour, and humbly ventures to think some disagreeable dream has disturbed your majesty’s repose.’

“Abou Hassan burst into such a violent fit of laughter at this speech of Mesrour’s that he fell back on his pillow, to the great amusement of the real caliph, who would have laughed as loudly as did the pretended one, but for the fear of putting an end to the pleasant scene which he had determined to have exhibited before him.

“After he had laughed till he was out of breath, Abou Hassan sat up again in his bed, and speaking to a little eunuch as black as Mesrour, cried, ‘Hark ye, tell me who I am.’ ‘O mighty sovereign,’ said the little eunuch, in a very humble manner, ‘your majesty is the Commander of the Faithful, and vicar upon earth of the Lord of both worlds.’ ‘Thou art a little liar, thou sooty-face!’ replied Abou Hassan.

“He then called one of the ladies who was nearer to him than the rest. ‘Come hither,’ said he, as he held out his hand towards her, ‘take the end of my finger and bite it, O thou fair one, that I may feel whether I am asleep or awake.’

“The damsel, who knew the caliph from his hiding place saw all that was going on, was delighted with an opportunity of showing how well she could play her part where the business was to afford her master amusement. She came towards Abou Hassan with the most serious air imaginable, and closing her teeth upon the end of his finger, which he had held out to her, she bit it pretty sharply.

“Abou Hassan drew back his hand in a hurry. ‘I am not asleep,’ he cried, I am most assuredly not asleep. By what miracle have I become caliph in one night? This is the most surprising, the most marvellous thing in the world.’ Speaking again to the same damsel he resumed, ‘Now, in the name of Allah, in whom you put your trust, as I also do, I beseech you tell me exactly the truth. Am I really and truly the Commander of the Faithful?’ ‘Your majesty,’ replied she, ‘is in truth and actually the Commander of the Faithful; and we, who are your slaves, are all amazed to think what can make your majesty doubt the fact.’ ‘You lie.’ replied Abou Hassan, ‘I know very well who I am.’

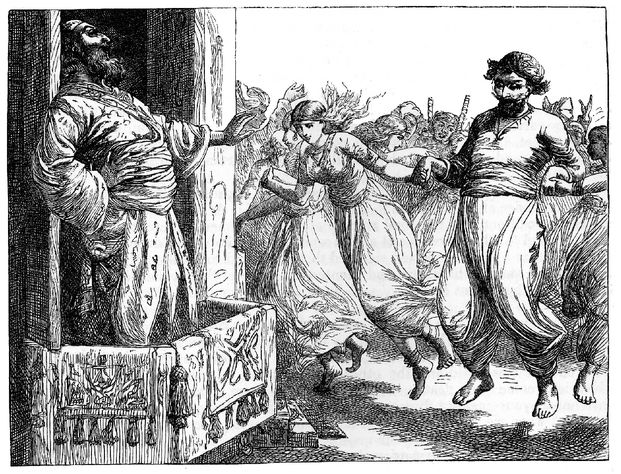

“As the chief of the eunuchs perceived that Abou Hassan meant to rise, he offered his hand to assist him in getting out of bed. As soon as the pretended caliph stood up, the whole chamber resounded with the salutation which all the officers and ladies pronounced with acclamation in these words: ‘O Commander of the Faithful, in the name of Allah, we wish your majesty good morning.’

“ ‘Oh, Heavens!’ cried Abou Hassan, ‘what miracle is this! Last night was I Abou Hassan, and this morning I am the Commander of the Faithful! I cannot at all understand this very sudden and surprising change.’ The officers whose business it was to dress the caliph speedily performed their office. When this was accomplished, as the other officers, the eunuchs, and the ladies, had ranged themselves in two lines, extending to the door through which he was to go into the council chamber, Mesrour led the way, and Abou Hassan followed. The arras was drawn back, and the door opened by an usher. Mesrour entered the council chamber, and went on before Abou Hassan quite to the foot of the throne, where he stopped to assist him in ascending it. He supported the caliph by placing his hand under his shoulder on one side, while another officer, who followed, assisted him in the same way on the other.

“Thus Abou Hassan sat on the royal throne amidst the acclamations of the attendants, who wished him all kinds of happiness and prosperity; and looking to the right and left he saw the officers of the guards ranged in two rows in exact military order.

“Directly Abou Hassan entered the council chamber, the caliph quitted the closet in which he had been concealed, and passed to another closet from whence he could see and hear all that took place in the council when the grand vizier presided there instead of him, if at any time it was inconvenient for him to be there in person. He was not a little diverted to see Abou Hassan representing him upon the throne, and presiding with as much gravity as he could himself have shown.

“When Abou Hassan had taken his seat, the grand vizier, who was present, prostrated himself at the foot of the throne, and, as he rose, said in a solemn voice: ‘O Commander of the Faithful, may Allah pour upon your majesty all the blessings of this life, and receive you into paradise in the next, and cast your enemies into the flames of hell!’

“After all that had happened to him since he awoke, and what he had just heard from the mouth of the grand vizier, Abou Hassan no longer doubted that his wish had been fulfilled, and that he was really the caliph. So without examining how, or by what means this unexpected transformation had been brought about, he immediately began to exercise his power. Looking at the grand vizier with profound gravity, he asked him whether he had anything to report.

“O Commander of the Faithful, replied the grand vizier, ‘the emirs, the viziers, and the other officers who belong to your majesty’s council, are at the door, anxiously waiting till you shall give them permission that they may enter, and pay their accustomed respects.’ Abou Hassan immediately gave the word to open the door, and the grand vizier, turning round, said to the chief usher who stood expectant, ‘O chief usher, the Commander of the Faithful enjoins you to do your duty.’

“The door was opened; and at once the viziers, the emirs, and the principal officers of the court, all in their magnificent habits of ceremony, entered in exact order. They came forward to the foot of the throne, and paid their respects to Abou Hassan, each according to his rank, bending the knee, and prostrating themselves with their faces to the ground, just as they would have done in presence of the caliph himself. They saluted him by the name of Commander of the Faithful, according to the instructions given by the grand vizier. They then took their places in turn when each had gone through this ceremony. When this was ended, and they had all returned to their places, there was a profound silence.

“Then the grand vizier, standing before the throne, began to make his report of various matters from a number of papers which he held in his hand. This report was a matter of routine, and of little consequence. Nevertheless the caliph was in constant admiration of Abou Hassan’s conduct; for the new caliph never was at a loss, nor appeared at all embarrassed. He gave just decisions upon the questions which came before him; for his good sense suggested whether he was to grant or refuse the demands that were made.

“Before the vizier had finished his report, Abou Hassan caught sight of the chief officer of the police, whom he had often seen sitting in his place. ‘Stay a moment,’ said he, interrupting the grand vizier, ‘I have an order of importance to give immediately to the officer of the police.’

“This officer, who had his eyes fixed upon Abou Hassan, and who perceived that he looked at him in particular, hearing his name mentioned, rose immediately from his place, and gravely approached the throne, at the foot of which he prostrated himself with his face towards the ground. ‘O officer,’ said Abou Hassan to him, when he had raised himself, ‘go immediately, without loss of time, to such a street in such a quarter of the town,’ and he mentioned the name of his own street. ‘In this street is a mosque, where you will find the Iman and four old grey-beards. Seize their persons, and let the four old men have each a hundred strokes on the feet, and let the Iman have four hundred. Thereupon you shall cause all the five to be clothed in rags and mounted each on a camel, with their faces turned towards the tail. Thus equipped, you shall have them led through the different quarters of the town preceded by a crier, who shall proclaim with a loud voice, “This is the punishment for those who meddle with affairs which do not concern them, and who make it their business to sow dissension among neighbouring families, and to cause strife and mischief.” I command you, moreover, that you enjoin them to leave the part of the town in which they now live, and forbid them ever to set foot again in the place whence they are driven. While your deputy is leading them in the procession I have just ordered, you must return to report to me the execution of my commands.’

“The officer of police placed his hand upon his head, to signify that he was ready to execute the order he had received, and should expect to lose his head if he failed in any point. He prostrated himself a second time before the throne, then rose and went away.

“The order thus judiciously given gave the caliph great satisfaction; for he was now convinced that Abou Hassan had been in earnest in wishing to punish the Iman and his four old counsellors, when he declared that was the original motive for his wishing that he might have the caliph’s power for a single day.

“The grand vizier went on with his report, which he had very nearly ended, when the officer of the police presented himself to give an account of what he had done. He approached the throne, and, after the usual ceremony of prostration, said to Abou Hassan: ‘O Commander of the Faithful, I found the Iman and the four old men in the mosque of which your majesty spoke, and to prove that I have duly executed the orders I received from your majesty, I bring a written account of the proceeding, signed by many principal people of that part of the town who were witnesses. ’ So saying, he took from his bosom a paper, and gave it to the pretended caliph.

“Abou Hassan took the paper and read it from beginning to end, even to the names of the witnesses, all of whom were people whom he knew; and when he had finished, he said with a smile to the officer of the police: ‘You have done well; I am satisfied and pleased; resume your place.’ And he added to himself, with an air of satisfaction, ‘Hypocrites who undertake to comment upon my actions, and think it wrong that I should receive and entertain respectable people at my house, richly deserve this disgrace and punishment.’ The caliph, who watched him, saw into his mind and highly approved of the proceedings of his substitute.

“After that Abou Hassan addressed the grand vizier: ‘Let the grand treasurer,’ said he, ‘make up a purse of a thousand pieces of gold, and go with it into the quarter of the city whither I sent the officer of the police, and give it to the mother of one Abou Hassan, called the Reveller. The man is well known throughout that quarter by that name; any man will show you his house. Go, and return quickly.’

“The grand vizier Giafar put his hand to his head to mark his readiness to obey; and after prostrating himself before the throne, departed, and went to the grand treasurer, who gave him the purse. He ordered one of the slaves who attended him to take it, and proceed to convey it to Abou Hassan’s mother. On coming to her house, he said the caliph had sent her this present, and departed without explaining himself farther. Abou Hassan’s mother was much surprised at receiving the purse, as she could not conceive what should induce the caliph to make her so handsome a present; for she knew not what was passing at the palace.

“During the absence of the grand vizier, the officer of the police made a report of many matters in his department; and this lasted until the vizier returned. As soon as Giafar reached the council-chamber, and had assured Abou Hassan that he had executed his commission, Mesrour, the chief of the eunuchs, who, after he had conducted Abou Hassan to the throne had passed into the inner apartments of the palace, came back and made a sign to the viziers, emirs, and all the officers, that the council was ended, and that every one might retire. They accordingly withdrew, after taking their leave by making a profound reverence at the foot of the throne, in the same order as they observed upon their entrance. There then remained with Abou Hassan only the officers of the caliph’s guard and the grand vizier.

“Abou Hassan did not continue long on the throne of the caliph. He descended from it as he had mounted it, with the assistance of Mesrour and of another officer of the eunuchs. Each of his companions took him by an arm and attended him to the apartment in which he was at first. Then Mesrour, walking before him to show him the way, led him into an inner room, where a table was set out. The door of the apartment was open, and a great many eunuchs ran to tell the female musicians that the pretended caliph was coming. They immediately began a very harmonious concert of vocal and instrumental music, which delighted Abou Hassan to such a degree that he was transported with satisfaction and joy, and was quite at a loss what to think of all he saw and heard. ‘If this is a dream,’ said he to himself, ‘it is a dream of a long continuance. But it cannot be a dream,’ continued he, ‘I am perfectly sensible, I make use of my understanding—I see—I walk—I hear. Be it what it may, I am in the hands of Heaven, and must be content. Still, I cannot possibly believe that I am not the Commander of the Faithful; for none but the Commander of the Faithful could be surrounded with the magnificence I find here. The honours and respect which have been, and are still paid to me, and the rapid execution of my orders, are clear proofs of it.’

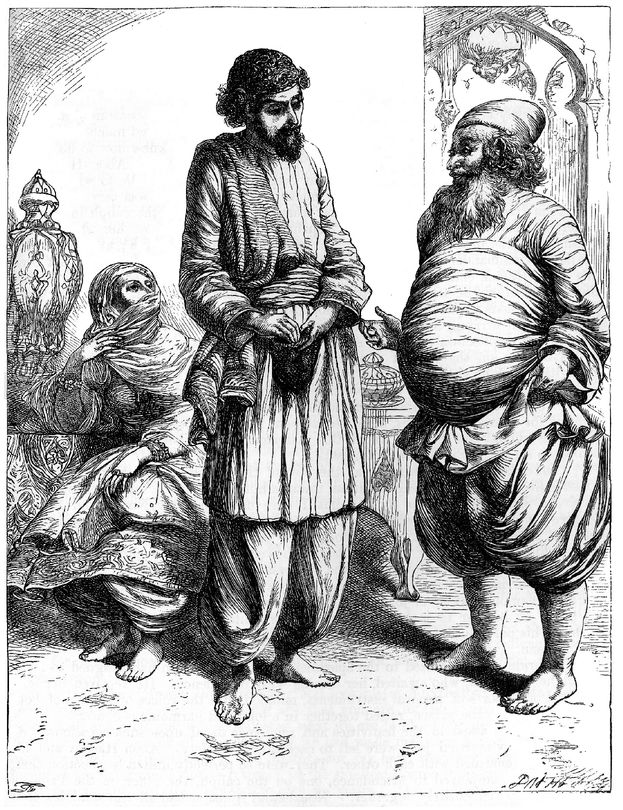

“Abou Hassan was at last convinced that he was the caliph and the Commander of the Faithful; and this conviction was confirmed in him when he found himself in a very large and richly furnished saloon. Gold shone on all sides, intermixed with the most vivid colours. Seven bands of female musicians, all women of the most exquisite beauty, were posted around this saloon. Seven golden lustres, with the same number of branches, hung from different parts of the ceiling, which was painted in a beautiful pattern—a skilful mixture of gold and azure. In the midst was a table on which gleamed seven large dishes of massive gold, which perfumed the room with the odour of the richest spices used in seasoning the several delicacies. Seven young and very beautiful damsels, dressed in habits of the richest stuffs and most brilliant colours, stood round the table. Each held a fan in her hand, which was for the purpose of refreshing their lord the caliph while he sat at table.

“If ever mortal was delighted, that mortal was Abou Hassan when he entered this magnificent saloon. At every step he paused to look about him, and contemplate at his leisure all the wonderful things which were presented to his view. Each moment he turned from side to side in sheer amazement, to the high delight of the caliph, who watched him with the utmost attention. At length he walked forward towards the middle of the room and took his place at the table. Immediately the seven beautiful damsels began agitating the air with their fans to refresh the new caliph. He looked at them all in succession; and after admiring the graceful ease with which they performed their office, he said to them, with a gracious smile, that he supposed one of them at a time would be able to give him all the air he wanted; and he desired that the other six should place themselves at the table with him, three on his right and three on his left, and give him their company. The table was round; and Abou Hassan placed these fair companions in such a manner at it that whichever way he looked his eyes rested on objects of beauty and delight.

Abou Hassan and the seven damsels.

“At his behest the six damsels placed themselves round the table. But Abou Hassan perceived that out of respect to him they forbore to eat. This induced him to help them himself, inviting and pressing them to eat in the most obliging manner. He desired to know their names, and each in turn replied to his questions.

“Their names were Neck-of-Alabaster, Lip-of-Coral, Fair-as-Moonlight, Bright-as-Sunshine, Eye’s-desire, Heart’s-delight. He put the same question to the seventh, who held the fan, and she answered that her name was Sugar-Cane. The agreeable things he said to each of them on the subject of their names showed that he had abundance of wit; and this display of his powers greatly heightened the esteem which the caliph had already entertained for him.

“When the damsels saw that Abou Hassan had ceased eating, one of them said to the eunuchs who were in waiting: ‘The Commander of the Faithful desires to walk into the saloon where the dessert is prepared; let water be brought.’ They all rose from the table at the same time; and one took from the hands of the eunuchs a golden basin, another a pitcher of the same metal, the third a napkin, and these they presented on their knees to Abou Hassan, who was still sitting, that he might have an opportunity of washing his hands. Thereupon he rose; and at the same moment an eunuch drew back the arras, and opened the door of another saloon into which he was to go.

“Mesrour, who had not quitted Abou Hassan, walked before him, and conducted him into a saloon as large as that he had left, but adorned with a variety of splendid pictures, and ornamented in quite a different manner, with vases of gold and silver. The carpets and other furniture were of the most costly kind. In this saloon there were also seven other bands of female musicians, different from the former, and these seven choirs of music began a new concert the moment Abou Hassan appeared. This saloon was furnished with seven other large lustres; and on the table in the middle stood seven large golden basins, in which every sort of fruit in season, the finest, best chosen, and most exquisite was piled up in pyramids; and round the table stood seven other young women more beautiful than the first, each with a fan in her hand.

“These new splendours raised in Abou Hassan’s mind a still greater admiration than he had felt before; and he paused for a moment manifesting the deepest surprise and astonishment. At length he reached the table, and when he was seated at it and had surveyed the seven damsels very leisurely one after another, with a sort of embarrassment which showed he could not tell to whom among them to give the preference, he ordered them all to lay aside their fans and to sit down and eat with him, saying, ‘that the heat was not so troublesome to him as to make him require their services.’

“When the damsels had taken their places on either side of Abou Hassan, he at once proceeded to inquire their names; and he found that they had different names from those of the seven in the former saloon, but that their names also marked some excellence of mind or body by which they were distinguished from each other. This amused him extremely; and he showed his wit in the lively and appropriate speeches he used when he offered to each, in turn, some fruit of the different sorts before him. To her who was called Heart’s-chain he gave a fig, saying: ‘Eat this for my sake, and make the chains lighter which I have worn from the moment I first saw you.’ And giving some grapes to Soul’s-grief, he said, ‘Take these grapes upon condition that you ease the grief I endure from the love with which you have inspired me;’ and he addressed a similar compliment to each of the other damsels. By his behaviour on this occasion Abou Hassan made the caliph, who was much pleased with all he did and all he said, more and more delighted; for Haroun Alraschid rejoiced greatly at having found in Abou Hassan a man who could so agreeably amuse him, and at the same time furnish him with the means of knowing his character more thoroughly.

When Abou Hassan had eaten of those sorts of fruit on the table which he liked best, he rose; and immediately Mesrour, who never quitted him, again walked before him, and led him into a third saloon, furnished, decorated, and enriched in the same magnificent manner as the two former.

“There Abou Hassan found seven other bands of music, and seven other damsels, waiting round a table, set out with seven golden basins containing liquid sweetmeats of various sorts and colours. After stopping to look at the multitude of new objects for admiration he encountered on all sides, he walked up to the table amidst the loud harmony of the seven bands of music, which ceased when he had taken his seat. At his command these seven damsels also took their places at the table with him. And as he could not dispense these liquids with the same grace, and with the same polite attention he had shown in distributing the fruits, he begged that the ladies would themselves make choice of such as they liked best. He asked their names too; and he was not less pleased with these than with those of the former damsels; for the variety of their appellations furnished him with new matter for conversing with the ladies, and addressing them with tender expressions, which gave them as much pleasure as this new proof of Abou Hassan’s wit gave the caliph, who did not lose a word that he said.

“The day was drawing towards a close when Abou Hassan was conducted into a fourth saloon. This apartment was decorated like the rest with the most costly and most magnificent furniture. Here, too, were seven grand lustres of gold with lighted tapers; and the whole room was illuminated by a vast number of other lights, which had a novel and wonderful effect. Abou Hassan found in this last saloon, as he had found in all the others, seven bands of female musicians. These began to play a strain of a gayer cast than had been performed in the other saloons, and one which seemed intended to inspire cheerfulness and mirth. Here, too, he saw seven other damsels, who stood in waiting round a table. On this table glittered seven basins of gold, filled with cakes and pastry, with all sorts of dry sweetmeats, and with a number of other compounds, provocative of drinking. But Abou Hassan observed here what he had not seen in the other saloons; this was a side-board, upon which were seven large flagons of silver filled with the most exquisite wines; and seven glasses of the finest rock crystal, of excellent workmanship, stood near each of these flagons.

In the three first saloons Abou Hassan had drunk only water, in compliance with the custom observed at Baghdad, equally by the common people, by the upper ranks, and by the court of the caliph, namely, to drink wine only at night. All those who drink it before evening are looked upon as dissipated persons; and they dare not appear in the day time. This custom is the more to be commended, as during the day a man requires a clear head to transact business; and, again, as wine is not taken till night at Baghdad, drunken people are never seen making disturbances in open day in the streets of that city.

“Abou Hassan entered this fourth saloon and walked up to the table. When he was seated he remained a long time in a kind of ecstasy of admiration at the seven damsels who stood about him, and whom he thought still more lovely than those he had seen in the other saloons. He had great desire to know the name of each of them, but as the loud sound of the music, and especially of the cymbals, which were used in all the bands, did not allow his voice to be heard, he clapped his hands to put an end to the performance; and instantly there was a profound silence.

“Thereupon he took the hand of the damsel who was nearest him on the right. He made her sit down, and after presenting her with a rich cake, he asked her name. ‘Commander of the Faithful,’ answered the damsel, ‘I am called Cluster-of-Pearls.’ ‘You could not have a better name,’ cried Abou Hassan, ‘or one more expressive of your charms. Without prejudice to those who gave you this name, I must think your beautiful teeth, certainly surpass the finest-coloured pearls in the world. Cluster-of-Pearls,’ added he, ‘since that is your name, do me the favour take a glass, fill it, and let me drink it from your fair hand.’

“The damsel went instantly to the side-board, and came back with a glass of wine, which she presented to Abou Hassan with all imaginable grace. He took it with pleasure, and looking at her tenderly said, in a voice of admiration, ‘Cluster-of-Pearls, I drink your health; I desire you would fill the glass for yourself and pledge me in return.’ She quickly ran to the side-board and returned with a glass in her hand; but before she drank Cluster-of-Pearls sung a song, which delighted her hearer not less from its novelty than by the charm of her voice, which was still more fascinating.

When Abou Hassan had drunk he took from the basins a supply of what he liked best, and presented it to another damsel, whom he desired to come and sit near him. He enquired her name also. She answered, that her name was Morning-Star. ‘Your fine eyes,’ resumed he, ‘are brighter and more brilliant than the star whose name you bear. Go, and do me the favour to bring me a glass of wine;’ she complied in a moment, with the best grace possible. He paid a similar compliment to the third damsel who was called Light-of-Day, as well as to all the rest, who each presented him wine which he drank, to the high delight of the caliph.

“When Abou Hassan had emptied as many glasses as there were damsels, Cluster-of-Pearls, to whom he had first spoken, went to the side-board and took a glass which she filled with wine, after having thrown into it a little of the powder which the caliph had made use of the day before. Presently she came and presented it to him with these words: ‘Commander of the Faithful,’ I entreat your majesty, by my anxiety for the preservation of your health, to take this glass of wine, and before you drink it to hear a song which I dare flatter myself will not be disagreeable to you. I composed it only this morning, and no one has yet heard me sing it.’ ‘I grant your request with pleasure,’ said Abou Hassan, as he took the glass which she presented to him; ‘and as Commander of the Faithful I lay my injunctions upon you to sing, as I feel assured that so charming a person as you can say nothing but what is most agreeable and very lively.’

“The damsel took her lute and sang a song, accompanying herself on this instrument with so much accuracy, grace, and expression, that she kept Abou Hassan entranced from beginning to end. He thought her song so charming that he called for it a second time, and was no less pleased with it than he had been before.

“When she had finished singing, Abou Hassan, who was desirous of praising her as she deserved, drank off at a draught the glass of wine she had filled for him. Then turning his head towards the damsel to speak to her, he was suddenly overcome by the effect of the powder which he had taken, and could only open his mouth without uttering a single word distinctly. Presently his eyes closed; and letting his head fall upon the table, like a man thoroughly overcome with sleep, he became as completely forgetful of all outward things as he had been the day before, about the same time when the caliph had administered the powder to him, and one of the damsels near him caught the glass which he let fall from his hand. The caliph, who had derived an amount of amusement beyond his expectation from the events of the day, and who saw what happened now as well as whatever Abou Hassan had done before, came out of his closet and appeared in the saloon, quite delighted at having succeeded so well in his design. He first ordered that the caliph’s habit in which Abou Hassan had been dressed in the morning, should be taken from him; and that he should be clothed again in the garments which he had worn twenty-four hours before, at the time the slave, who accompanied the caliph, had brought him to the palace. He ordered the same slave to be called; and upon his appearing he said, ‘Take charge once more of this man,’ and carry him back to his own bed as silently as you can; and when you come away be careful to leave the door open.’

“The slave took up Abou Hassan, carried him off by the secret door of the palace, and placed him in his own house as the caliph had ordered him. Then he returned in haste to give an account of what he had done. Then the caliph said: ‘Abou Hassan wished to be in my place for one day only that he might punish the Iman of the mosque in his neighbourhood, and the four scheiks, or old men, whose conduct had displeased him; I have procured him the means of doing what he wished. Therefore he ought to be satisfied.’

“Abou Hassan, who had been deposited on his sofa by the slave, slept till very late the next day. He did not awake until the effect of the powder which had been put into the last glass he drank had passed away. Then, upon opening his eyes, he was very much surprised to find himself at his own house. ‘Cluster-of-Pearls! Morning-Star! Break-of-day! Coral-lips! Moonshine!’ cried he, calling the damsels of the palace who had been sitting with him each by their name as he could recollect them, ‘Where are you? Come to me!’

“Abou Hassan called as loudly as he could. His mother, who heard him from her apartment, came running up at the noise he made; ‘What’s the matter with you, my son?’ she asked. ‘What has befallen you?’ At these words Abou Hassan raised his head, and looking at his mother with an air of haughtiness and disdain, replied, ‘Good woman, who is the person you call your son?’ ‘You are he,’ answered the mother, with much tenderness, ‘are not you my son, Abou Hassan? It would be the most extraordinary thing in the world if, in so short a time, you should have forgotten it.’ ‘I your son, you execrable old woman!’ cried Abou Hassan, ‘you know not what you are saying. You are a liar. I am not the Abou Hassan you speak of: I am the Commander of the Faithful.’

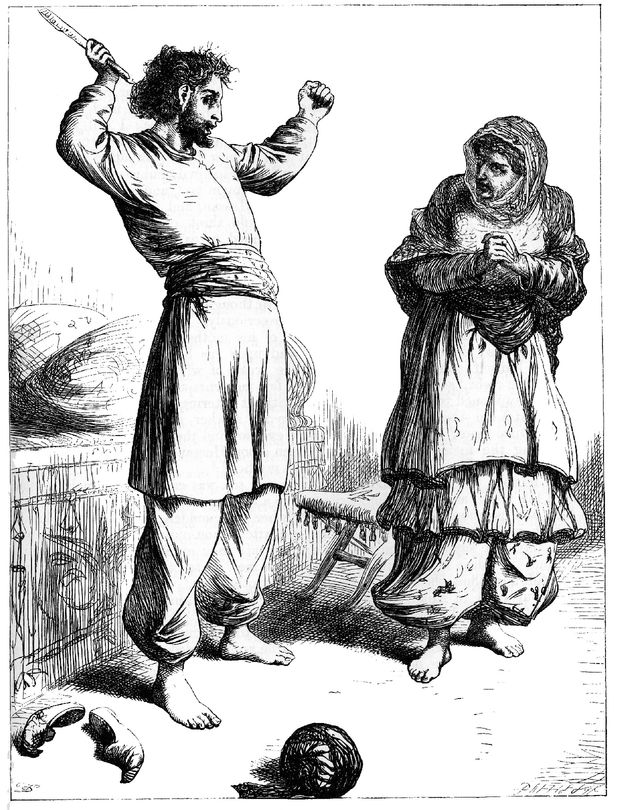

Abou Hassan and his mother.

“ ‘Be silent, my son,’ rejoined the mother, ‘you do not consider what you say: to hear you talk men would take you for a madman.’ ‘You are yourself a mad old woman,’ replied Abou Hassan, ‘I am not out of my senses, as you suppose; I tell you again I am Commander of the Faithful, and vicar upon earth of the Lord of both worlds.’ ‘Ah, my son!’ cried the mother, ‘how comes it that I now hear you utter words which clearly prove that you are not in your right mind? What evil genius possesses you that you hold such language. The blessing of Allah be upon you, and may he deliver you from the malice of Satan! You are my son, Abou Hassan, and I am your mother.’

“After having given him all the proofs she could think of to convince him of his error in order to bring him to himself, she continued to expostulate in these words: ‘Do you not see that the chamber you are now in is your own, and not the chamber of a palace fit for the Commander of the Faithful; and that living constantly with me you have dwelt in this house ever since you were born! Reflect upon all I have been saying to you, and do not let your mind be troubled with thoughts which are not, and cannot be true; once more, my son, consider the matter seriously.’

“Abou Hassan heard these remonstrances of his mother with composure. He sat with his eyes cast down, and resting his head upon his hand, like a man who was recollecting himself and trying to discover the truth of what he saw and heard: ‘I believe you are right,’ said he, to his mother, a few moments afterwards, looking up as if he had been awakened from a deep sleep, but without altering his posture. ‘It seems,’ said he, ‘that I am Abou Hassan, that you are my mother, and that I am in my own chamber. Once more,’ added he, throwing his eyes around the chamber, and attentively contemplating the furniture it contained, ‘I am Abou Hassan; I cannot doubt it, nor can I conceive how I could take this fancy into my head.’

“His mother thought in good earnest that her son was cured of the malady which disturbed his mind, and which she attributed to a dream. She was preparing to laugh with him, and question him about his dream, when on a sudden he sat up, and looking at her with an angry glance, cried: ‘Thou old witch, thou old sorceress, thou knowest not what thou art saying; I am not thy son, nor art thou my mother. Thou deceivest thyself, and thou dost endeavour to impose upon me. I tell thee I am Commander of the Faithful, and thou shalt not make me believe otherwise.’ ‘For Heaven’s sake, my son, put your trust in Allah, and refrain from holding this kind of language, lest some mischief befall you. Let us rather talk of something else. Allow me to tell you what happened yesterday to the Iman of our mosque, and to the four scheiks of our neighbourhood. The officer of the police caused them to be apprehended, and after having given them each in turn I know not how many strokes on the feet, he ordered it to be proclaimed by the crier, that this was the punishment of men who meddled with affairs that did not concern them, and who made it their business to sow dissension among the families of their neighbours. Then he caused them to be led through all parts of the town, while the same proclamation was repeated before them, and he forbade them ever to set foot again in our neighbourhood.’

“Abou Hassan’s mother, who could not imagine her son had any concern in the event she was relating, had purposely turned the conversation, and supposed that the narration of this affair would be a likely mode of effacing the whimsical delusion under which he laboured of being the Commander of the Faithful.

“But the effect proved quite otherwise, and the recital of this story, far from effacing the notion which he now entertained, that he was the Commander of the Faithful, served only to recall it to his mind, and to impress still more deeply on his imagination the firm conviction that it was not a delusion, but a real fact. Thus, the moment his mother had finished her story, Abou Hassan exclaimed, ‘I am no longer your son, nor Abou Hassan, I am assuredly the Commander of the Faithful, and it is not possible for me to have any furthur doubt after what you yourself have just told me. Know then, that it was by my orders that the Iman and the four scheiks were punished in the manner you have related; I tell you, in good truth, I am the Commander of the Faithful; say therefore no longer that it is a dream. I am not now asleep, nor was I dreaming at the time I am telling you of. You have greatly pleased me by confirming what the officer of the police, to whom I gave the orders for the punishment you described, had already reported to me; that is to say, that my commands were punctually executed; and I am the more pleased at this because this Iman and these four scheiks were consummate hypocrites. I should be glad to know who it was that brought me here. Allah be praised for everything. The truth is this, that I am most assuredly the Commander of the Faithful, and all your reasoning will never persuade me to the contrary.’

“His mother, who could not guess or even imagine why her son maintained with so much obstinacy and so much confidence that he was the Commander of the Faithful, felt quite assured that he had lost his senses when she heard him assert things which in her mind were so entirely beyond all belief, though in that of Abou Hassan they had a good foundation. Under this persuasion she said, ‘My son, I pray Heaven to pity and have mercy upon you. Cease, my son, from talking a language so utterly devoid of common sense. Look up to Allah, and entreat him to pardon you, and give you grace to converse like a man in his senses. What would be said of you if you should be heard talking in this manner. Do you not know that walls have ears?’

“These remonstrances, far from softening Abou Hassan’s anger, served only to irritate him still more. He inveighed against his mother with greater violence than ever. ‘O old woman,’ said he, ‘I have already cautioned thee to be quiet. If thou continuest to talk any longer I will rise and chastise thee in a manner thou wilt remember all the rest of thy life. I am the caliph, the Commander of the Faithful, and thou art bound to believe me when I tell thee so.’ Then the poor mother, seeing that Abou Hassan was wandering still farther and farther from his right mind, instead of returning to the subject gave way to tears and lamentations. She bent her face and bosom; she uttered exclamations, which testified her astonishment and deep sorrow at seeing her son in such a dreadful position—lunatic and deprived of understanding.

“Abou Hassan, instead of being calm, and suffering himself to be affected by his mother’s tears, on the contrary, forgot himself so far as to lose all sort of natural respect for her. He rose and suddenly seizing a stick he came towards her with his uplifted hand, raging like a madman. ‘Thou cursed old woman,’ said he, in his fury, and in a tone of voice sufficient to terrify any other than an affectionate mother, ‘tell me this moment who I am!’ ‘My son,’ answered his mother, looking most kindly at him, and far from being afraid, ‘I do not believe you so far abandoned by Allah as not to know the woman who brought you into the world, or to know who you yourself are. I am perfectly sincere in telling you that you are my son Abou Hassan, and that you are quite wrong in claiming for yourself a title, which belongs only to the caliph Haroun Alraschid, your sovereign lord and mine; and this is the more culpable, at a time when our monarch has been heaping benefits upon both you and me, by the present he sent me yesterday. In fact, I have to tell you that the grand vizier Giafar took the trouble yesterday to come hither to me, and putting into my hands a purse of a thousand pieces of gold, he bade me pray to Allah to bless the Commander of the Faithful, who made me this present; and does not this liberality concern you more than me, seeing I have but a few days to live?’

“At these last words Abou Hassan lost all command over himself. The circumstances of the caliph’s liberality, which his mother had just related, assured him he did not deceive himself, and convinced him more firmly than ever that he himself was the caliph, because the vizier had carried the purse by his own order. ‘What! thou old sorceress!’ cried he, ‘wilt thou not be convinced when I tell thee that I am the person who sent these thousand pieces of gold by my grand vizier Giafar, who merely executed the order which I gave him as Commander of the Faithful? Nevertheless, instead of believing me thou art seeking to make me lose my senses by thy contradictions, maintaining, with wicked obstinacy, that I am thy son. But I will not suffer thy insolence to be long unpunished.’ Upon this, in the height of his frenzy, he was so unnatural as to beat her most unmercifully with the stick he held in his hand.

“When his poor mother, who had not supposed her son would so quickly put his threats in execution, found herself beaten, she began to cry out for help as loudly as she could; and as the neighbours came crowding round, Abou Hassan never ceased striking her, calling out at every stroke, ‘Am I the Commander of the Faithful?’ And each time the mother affectionately returned, ‘You are my son.’

“Abou Hassan’s rage began to abate a little when the neighbours came into his chamber. The first who appeared at once threw himself between his mother and him; and snatching the stick from his hand cried out, ‘What are you doing, Abou Hassan? have you lost all sense of duty, or are you mad? Never did a son of your condition in life dare to lift his hand against his mother! And are not you ashamed thus to ill-treat her who so tenderly loves you?’

“Abou Hassan, still raging with fury, looked at the person who spoke without giving him any answer. Then casting his wild eyes on each of the others who had come in, he demanded, ‘Who is this Abou Hassan you are speaking of? Is it me you call by that name?’ This question somewhat disconcerted the neighbours. ‘How!’ replied the man who had just spoken, ‘do not you acknowledge this woman for the person who brought you up, and with whom we have always seen you living? in one word, do not you acknowledge her for your mother?’ ‘You are very impertinent,’ replied Abou Hassan; ‘I know neither her nor you; and I do not wish to know her. I am not Abou Hassan, I am the Commander of the Faithful; and if you do not know it yet, I will make you know it to your cost.’

“At this speech the neighbours were all convinced that he had lost his senses. And to prevent his repeating towards others the outrageous conduct he had been guilty of towards his mother, they seized him, and, in spite of his resistance, bound him hand and foot, and deprived him of the power of doing any mischief. But though he was thus bound, and apparently unable to hurt anybody, they did not think it right to leave him alone with his mother. Two of the company hastened immediately to the hospital for lunatics, to inform the keeper of what had happened. That officer came directly, with some of the neighbours, followed by a considerable number of his people, who brought with them chains, handcuffs, and a whip made of thongs of leather for the purpose of restraining the supposed lunatic.