APPENDIX

Aladdin and Ali Baba: An Introductory Note

The following tales from the Arabian Nights are among the most popular stories in the world. Both have been adapted, rewritten, abridged, and performed for the theater and the cinema many times over. Aladdin’s magic lamp and Ali Baba’s “open sesame” are household words, used, as perhaps few other catchphrases are, for a multitude of different situations and excuses. The tales’ other details, such as Ali Baba’s brother who is murdered and cut into four pieces, are among the most gruesome in the historical register of detective and murder stories.

As with nearly all of the Arabian Nights tales, these two were made popular in the West by Antoine Galland’s pioneering French translation. But despite their popularity and renown, current scholarship does not consider these tales to be truly part of the original Arabian Nights. For while the authenticity of the three hundred or so “core” stories can be corroborated by their appearance in multiple source manuscripts, a group of “orphan” stories—of which “The History of Aladdin, or the Wonderful Lamp” and “The History of Ali Baba, and of the Forty Robbers Who Were Killed by One Slave” are two—have no written source other than Galland’s manuscript. As Galland noted in his diary in 1709, the tales were narrated to him by a Syrian named Maronite Hanna Diyab, and it is unknown where Diyab got the tales.

Questions of authenticity aside, some properties of the “orphan” tales can be traced to “core” tales or to medieval European adaptations of the “core” tales, and their themes are sympathetic with Islamic times of urbanity and conquest. Aladdin’s birth in China and the Moroccan magician’s travels, for example, have historical antecedents in earlier travel accounts from the Islamic hinterland to China, in particular Ibn Battuta’s (died 1377) Muslim travelogue. The idea of the “open sesame” and its magical connotations relies on Babylonian lore, while the slave girl’s intelligence and presence of mind in the story of Ali Baba have many antecedents in the voluminous Book of Songs, by Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani (897-967), and other compendiums.

The “orphan” tales proved very responsive to readers’ tastes, predilections, aspirations, and needs. Their wide appeal derives from their plots and charming details, especially during times of change and transformation. Contemporary Western readers see their personal lives, including their challenges and expectations, reflected in the tales, which maintain an enduring hold on the reading public.

—Muhsin al-Musawi

THE HISTORY OF ALADDIN, OR THE WONDERFUL LAMP.

IN the capital of one of the richest and most extensive provinces of the great empire of China there lived a tailor whose name was Mustapha. This tailor was very poor. The profits of his trade barely sufficed for the subsistence of himself, his wife, and the one son whom Heaven had sent him.

“This son, whose name was Aladdin, had been brought up in a very negligent and careless manner, and had been so much left to himself that he had contracted many very bad habits. He was obstinate, disobedient, and mischievous, and regarded nothing his father or mother said to him. As a lad he was continually absenting himself from home. He generally went out early in the morning, and spent the whole day in the public streets, playing with other boys of his own age who were as idle as himself.

“When he was old enough to learn a trade, his father, who was too poor to have him taught any other business than his own, took him to his shop, and began to show him how to use his needle. But neither kindness nor the fear of punishment could restrain Aladdin’s volatile and restless disposition, nor could his father succeed in making him attend to his work. No sooner was Mustapha’s back turned than Aladdin was off, and returned no more during the whole day. His father frequently chastised him, but Aladdin remained incorrigible; and with great sorrow Mustapha was obliged at last to abandon him to his idle vagabond course. This conduct of his son’s gave him great pain; and the vexation of not being able to induce young Aladdin to pursue a proper and reputable course of life, brought on a virulent and fatal disease that at the end of a few months put a period to poor Mustapha’s existence.

“As Aladdin’s mother saw that her son would never follow the trade of his father, she shut up Mustapha’s shop, and sold off all his stock and implements of trade. Upon the sum thus realised, added to what she could earn by spinning cotton, she and her son subsisted.

“Aladdin was now no longer restrained by the dread of his father’s anger; and so regardless was he of his mother’s advice, that he even threatened her whenever she attempted to remonstrate with him. He gave himself completely up to idleness and vagabondism. He continued to associate with boys of his own age, and became fonder than ever of taking part in all their tricks and fun. He pursued this course of life till he was fifteen years old, without showing the least token of good feeling of any sort, and without making the slightest reflection upon what was to be his future lot. Affairs were in this state when, as he was one day playing with his companions, according to his custom, in one of the public places, a stranger who was going by stopped and looked attentively at him.

“This stranger was a magician, so learned and famous for his skill that by way of distinction he was called the African Magician. He was, in fact, a native of Africa, and had arrived from that part of the world only two days before.

“Whether this African Magician, who was well skilled in physiog nomy, thought he saw in the countenance of Aladdin signs of a disposition well suited to the purpose for which he had undertaken a long journey, or whether he had any other project in view, is uncertain; but he very cleverly obtained information concerning Aladdin’s family, discovered who he was, and ascertained the sort of character and disposition he possessed. When he had made himself master of these particulars he went up to the youngster, and, taking him aside from his companions, asked him if his father was not called Mustapha, and whether he was not a tailor by trade. ‘Yes, sir,’ replied Aladdin; ‘but he has been dead a long time.’

“On hearing this, the African Magician threw his arms round Aladdin’s neck, and embraced and kissed him repeatedly, while the tears ran from his eyes, and his bosom heaved with sighs. Aladdin, who observed his emotion, asked him what reason he had to weep. ‘Alas! my child,’ replied the magician, ‘how can I refrain? I am your uncle: your father was my most excellent brother. I have been travelling hither for several years; and at the very instant of my arrival in this place, when I was congratulating myself upon the prospect of seeing him and rejoicing his heart by my return, you inform me of his death. How can I be so unfeeling as not to give way to the most violent grief when I thus find myself deprived of all my expected pleasure? However, my affliction is in some degree lessened by the fact that, as far as my recollection carries me, I discover many traces of your father in your countenance; and, on seeing you, I at once suspected who you were.’ He then asked Aladdin where his mother lived; and, when Aladdin had informed him, the African Magician put his hand into his purse and gave him a handful of small money, saying to him: ‘My son, go to your mother, make my respects to her, and tell her that I will come and see her to-morrow if I have an opportunity, that I may have the consolation of seeing the spot where my good brother lived so many years, and where his career closed at last.’

“As soon as the African Magician, his pretended uncle, had quitted him, Aladdin ran to his mother, highly delighted with the money that had been given him. ‘Pray tell me, mother,’ he cried as he entered the house, ‘whether I have an uncle.’ ‘No, my child,’ replied she, ‘you have no uncle, either on your poor father’s side or on mine.’ ‘For all that,’ answered the boy, ‘I have just seen a man who told me he was my father’s brother and my uncle. He even wept and embraced me when I told him of my father’s death. And to prove to you that he spoke the truth,’ added he, showing her the money which he had received, ‘see what he has given me! He bade me also be sure and give his kindest greeting to you, and to say that if he had time he would come and see you himself to-morrow, as he was very desirous of beholding the house where my father lived and died.’ ‘It is true, indeed, my son,’ replied Aladdin’s mother, ‘that your father had brother once; but he has been dead a long time, and I never heard your father mention any other.’ After this conversation they said no more on the subject.

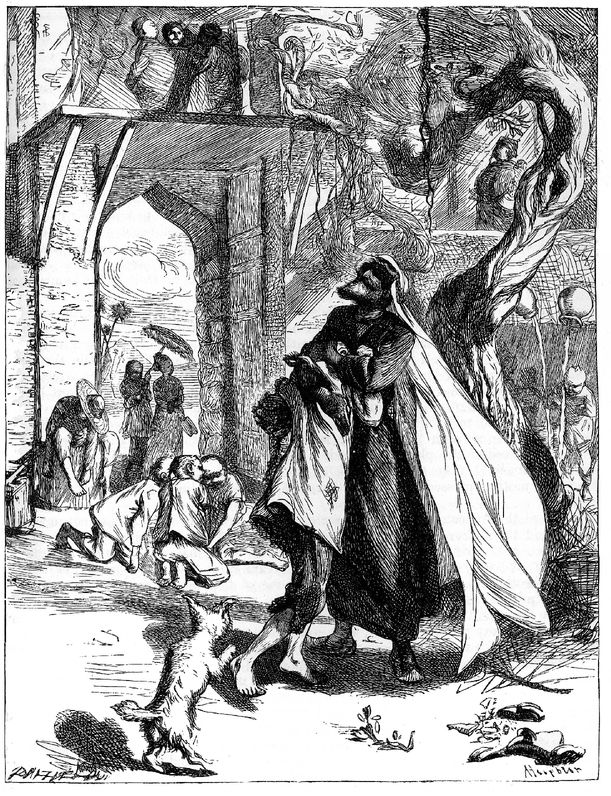

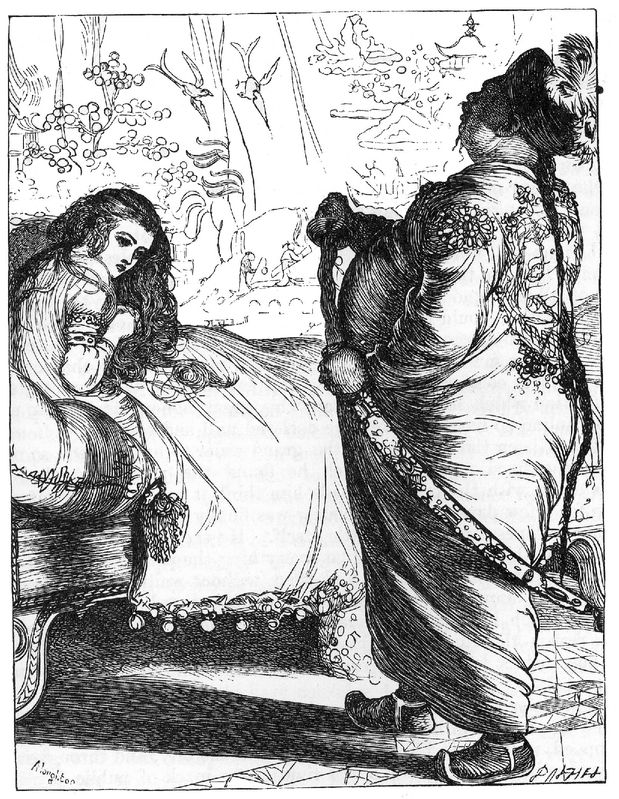

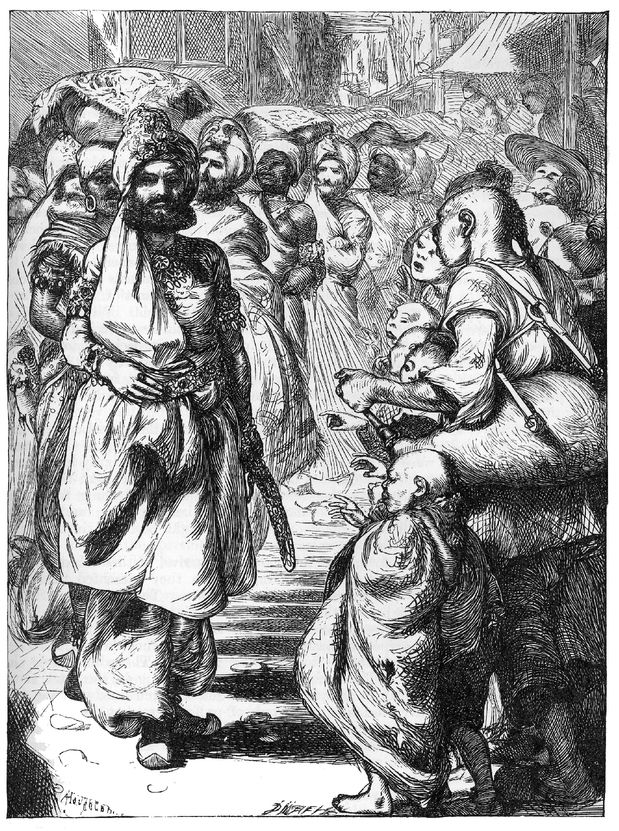

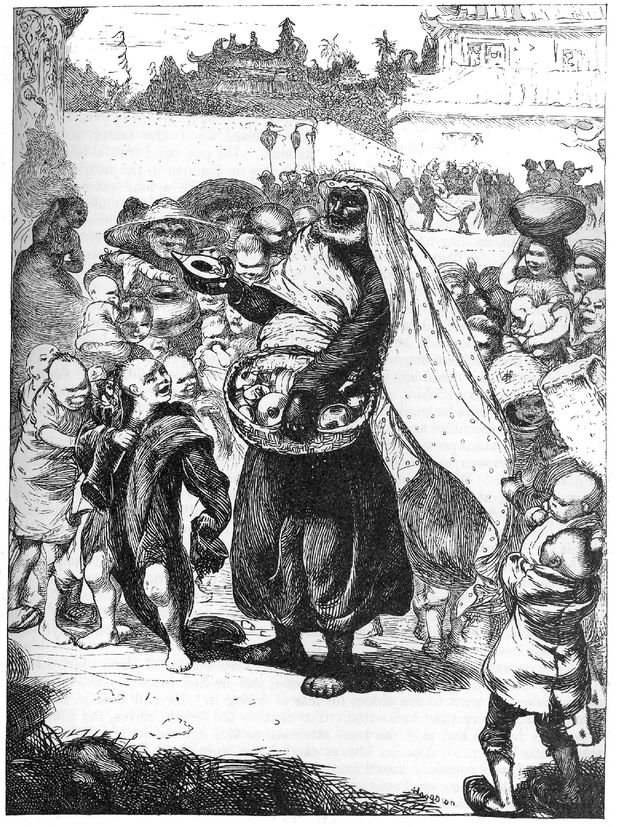

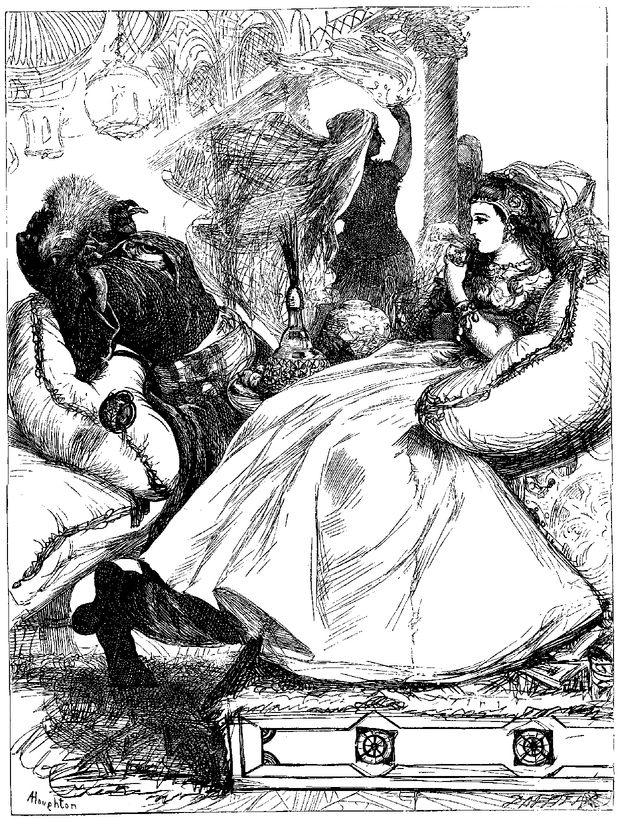

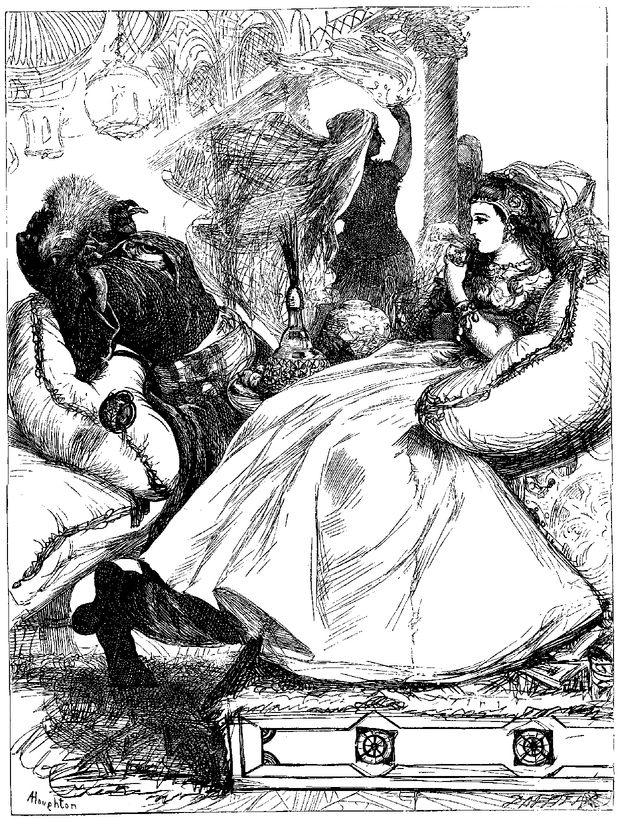

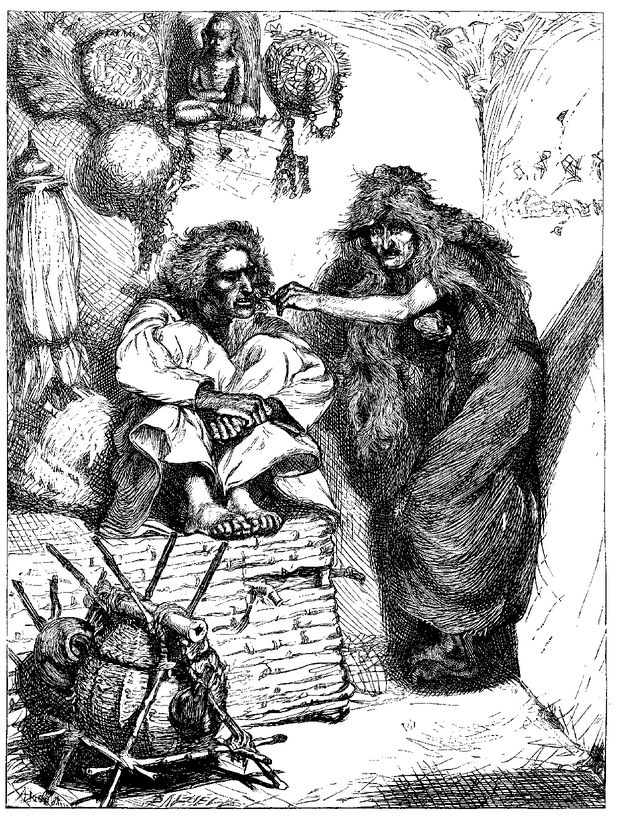

The African Magician embracing Aladdin.

“The next day the African Magician again accosted Aladdin while he was playing in another part of the city with three other boys. He embraced him as before, and putting two pieces of gold in his hand, said to him: ‘Take this, my boy, and carry it to your mother. Tell her that I intend to come and sup with her this evening, and that I send this money that she may purchase what is necessary for our entertainment; but first inform me in what quarter of the city I shall find your house.’ Aladdin gave him the necessary information, and the magician took his departure.

“Aladdin carried home the two pieces of gold to his mother; and, when he had told her of his supposed uncle’s intention, she went out and purchased a large supply of good provisions. And as she did not possess a sufficient quantity of china or earthenware to hold all her purchases, she went and borrowed what she wanted of her neighbours. She was busily employed during the whole day in preparing supper; and in the evening, when everything was ready, she desired Aladdin to go out into the street, and if he saw his uncle, to show him the way, as the stranger might not be able to find their house.

“Although Aladdin had pointed out to the magician the exact situation of his mother’s house, he was nevertheless very ready to go; but, just as he reached the door, he heard some one knock. Aladdin instantly opened the door, and saw the African Magician, who had several bottles of wine and different sorts of fruit in his hands, that they might all regale themselves.

“When the visitor had given to Aladdin all the things he had brought, he paid his respects to the boy’s mother, and requested her to show him the place where his brother Mustapha had been accustomed to sit upon the sofa. She pointed it out, and he immediately prostrated himself before it and kissed the sofa several times, while the tears seemed to run in abundance from his eyes. ‘Alas, my poor brother!’ he exclaimed, ‘how unfortunate am I not to have arrived in time to embrace you once more before you died!’ The mother of Aladdin begged this pretended brother to sit in the place her husband used to occupy; but he would by no means consent to do so. ‘No,’ he cried, ‘I will do no such thing. Give me leave, however, to seat myself opposite, that if I am deprived of the pleasure of seeing him here in person, sitting like the father of his dear family, I may at least look at the spot and try to imagine him present.’ Aladdin’s mother pressed him no further, but permitted him to take whatever seat he chose.

“When the African Magician had seated himself, he began to enter into conversation with Aladdin’s mother. ‘Do not be surprised, my good sister,’ he said, ‘that you have never seen me during the whole time you have been married to my late brother Mustapha, of happy memory. It is full forty years since I left this country, of which, like my brother, I am a native. In the course of this long period I have travelled through India, Persia, Arabia, Syria, and Egypt; and, after passing a considerable time in all the finest and most remarkable cities in those countries, I went into Africa, where I resided for many years. At last, as it is the most natural disposition of man, however distant he may be from the place of his birth, never to forget his native country, nor lose the recollection of his family, his friends, and the companions of his youth, the desire of seeing mine, and of once more embracing my dear brother, took so powerful a hold on my mind, that I felt sufficiently bold and strong once more to undergo the fatigue of this long journey. I therefore set about making the necessary preparations, and began my travels. It is useless to say how long I was thus employed, or to enumerate the various obstacles I had to encounter and all the fatigue I suffered before I came to the end of my labours. But nothing so much mortified me or gave me so much pain in all my travels as the intelligence of the death of my poor brother, whom I tenderly loved, and whose memory I must ever regard with a truly fraternal respect. I have recognised almost every feature of his countenance in the face of my nephew; and it was his likeness to my brother that enabled me to distinguish him from the other boys in whose company he was. He can inform you with what grief I received the melancholy news of my brother’s death. We must, however, praise Heaven for all things; and I console myself in finding him alive in his son, who certainly has inherited his most remarkable features.’

“The African Magician, who perceived that Aladdin’s mother was very much affected at this conversation about her husband, and that the recollection of him renewed her grief, now changed the subject, and, turning towards Aladdin, asked him his name. ‘I am called Aladdin,’ he answered. ‘And pray, Aladdin,’ said the magician, ‘what is your occupation? Have you learned any trade?’

“At this speech Aladdin hung his head, and was much disconcerted; but his mother seeing this, answered for him. ‘Aladdin,’ she said, ‘is a very idle boy. His father did all he could to make him learn his business, but could not get him to work; and since my husband’s death, in spite of everything I can say, Aladdin will learn nothing, but leads the idle life of a vagabond, though I remonstrate with him on the subject every day of my life. He spends all his time at play with other boys, without considering that he is no longer a child; and if you cannot make him ashamed of himself, and induce him to listen to your advice, I shall utterly despair that he will ever be good for anything. He knows very well that his father left us nothing to live upon; he can see that though I pass the whole day in spinning cotton, I can hardly get bread for us to eat. In short, I am resolved soon to turn him out of doors, and make him seek a livelihood where he can find it.’

“As she spoke these words, the good woman burst into tears. ‘This is not right, Aladdin,’ said the African Magician. ‘Dear nephew, you must think of supporting yourself, and working for your bread. There are many trades you might learn: consider if there be not any one you have an inclination for in preference to the rest. Perhaps the business which your father followed displeases you, and you would rather be brought up to some other calling. Come, come, don’t conceal your opinion; give it freely, and I may perhaps assist you.’ As he found that Aladdin made him no answer, he went on thus: ‘If you have any objection to learning a trade, and yet wish to grow up as a respectable and honest man, I will procure you a shop, and furnish it with rich stuffs and fine linens. You shall sell the goods, and with the profits that you make you shall buy other merchandise; and in this manner you will pass your life very respectably. Consult your own inclinations, and tell me candidly what you think of the plan. You will always find me ready to perform my promise.’

“This offer greatly flattered the vanity of Aladdin; and he was the more averse to any manual industry, because he knew well enough that the shops which contained goods of this sort were much frequented, and the merchants themselves well dressed and highly esteemed. He therefore hinted to the African Magician, whom he considered as his uncle, that he thought very favourably of this plan, and that he should all his life remember the obligation laid upon him. ‘Since this employment is agreeable to you,’ replied the magician, ‘I will take you with me to-morrow, and have you properly and handsomely dressed, as becomes one of the richest merchants of this city; and then we will procure a shop of the description I have named.’

“Aladdin’s mother, who till now had not been convinced that the magician was really the brother of her husband, no longer doubted the truth of his statement when she heard all the good he promised to do her son. She thanked him most sincerely for his kind intentions; and charging Aladdin to behave himself so as to prove worthy of the good fortune his uncle had led him to expect, she served up the supper. During the meal the conversation turned on the same subject, and continued till the magician, perceiving that the night was far advanced, took leave of Aladdin and his mother, and retired.

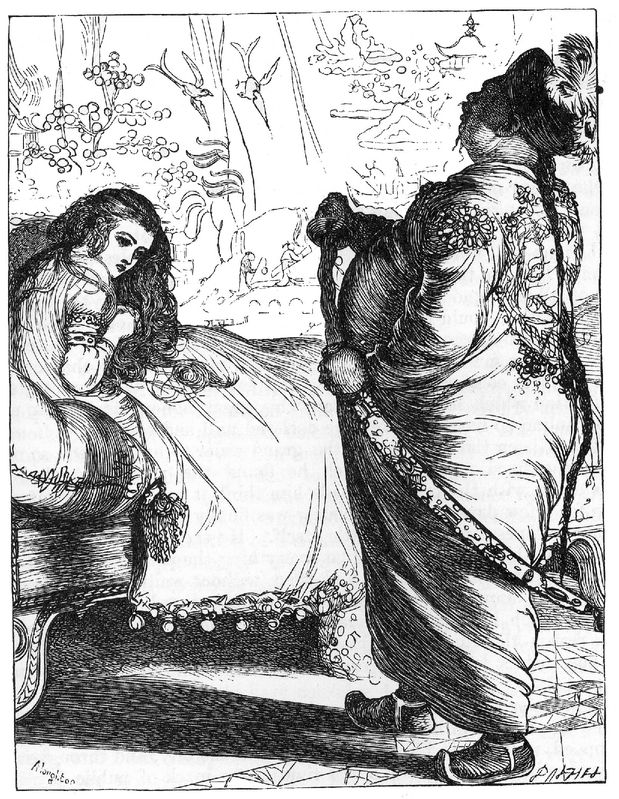

“The African Magician did not fail to return the next morning according to promise to the widow of Mustapha the tailor. He took Aladdin away with him, and brought the lad to a merchant’s where ready-made clothes were sold, suited to every description of people, and made of the finest stuffs. He made Aladdin try on such as seemed to fit him, and after choosing those he liked best, and rejecting others that he thought improper for him, he said, ‘Dear nephew, choose such as please you best out of this number.’ Delighted with the liberality of his new uncle, Aladdin made choice of a garment. The magician bought it, together with everything that was necessary to complete the dress, and paid for the whole without asking the merchant to make any abatement.

“When Aladdin saw himself thus handsomely dressed from head to foot, he overwhelmed his uncle with thanks; the magician on his part again promised never to forsake him, but to continue to aid and protect him. He then conducted Aladdin to the most frequented parts of the city, particularly to the quarter where the shops of the most opulent merchants were situated; and when he had come to the street where fine stuffs and linens were sold in the shops, he said to Aladdin, ‘You will soon become a merchant like those who keep these shops. It is proper that you should frequent this place, and become acquainted with them.’ After this he took him to the largest and most noted mosques, to the khans where the foreign merchants lived, and through every part of the sultan’s palace where he had leave to enter. When they had thus visited all the chief parts of the city, they came to the khan where the magician had hired an apartment. They found several merchants with whom he had made some slight acquaintance since his arrival, and whom he had now invited to partake of a repast, that he might introduce his pretended nephew to them.

“The entertainment was not over till the evening. Aladdin then wished to take leave of his uncle, and go home. The African Magician, however, would not suffer him to go alone. He went himself, and conducted Aladdin back to his mother’s. When she saw her son so handsomely dressed, the good woman was transported with joy. She invoked a thousand blessings on the magician, who had been at so great an expense on her dear child’s account. ‘O generous relation,’ she exclaimed, ‘I know not how to thank you for your great liberality. My son, I know, is not worthy of such generosity, and he will be wicked indeed if he ever proves ungrateful to you, or fails to behave in such a way as to deserve and be an ornament to the excellent position you are about to place him in. I can only say,’ added she, ‘I thank you with my whole soul. May you live many happy years, and enjoy the gratitude of my son, who cannot prove his good intentions better than by following your advice.’

“Aladdin,’ replied the magician, ‘is a good boy. He seems to pay attention to what I say. I have no doubt that we shall make him what we wish. I am sorry for one thing, and that is that I shall not be able to perform all my promises to-morrow. It is Friday, and on that day all the shops are shut. It will be impossible to-morrow either to take a shop or furnish it with goods, because all the merchants are absent and engaged in their several amusements. We will, however, settle all this business the day after to-morrow, and I will come here to-morrow to take Aladdin away with me, and show him the public gardens, in which people of reputation constantly walk and amuse themselves. He has probably hitherto known nothing of the way in which men pass their hours of recreation. He has associated only with boys, but he must now learn to live with men.’ The magician then took his leave and departed. Aladdin, who was delighted at seeing himself so well dressed, was still more pleased at the idea of going to the gardens in the suburbs of the city. He had never been beyond the gates, nor had he seen the neighbouring country, which was really very beautiful and attractive.

“The next morning Aladdin got up very early and dressed himself, in order to be ready to set out the very moment his uncle called for him. After waiting some time, which he thought an age, he became so impatient that he opened the door and stood outside to watch for his uncle’s arrival. The moment he saw the magician coming, he went to inform his mother of the fact; then he took leave of her, shut the door, and ran to meet his uncle.

“The magician received Aladdin in the most affectionate manner. ‘Come, my good boy,’ said he, with a smile, ‘I will to-day show you some very fine things.’ He led the boy out at a gate that led to some large and handsome houses, or rather palaces, to each of which there was a beautiful garden, wherein they had the liberty of walking. At each palace they came to he asked Aladdin if it was not very beautiful; but the latter often anticipated this question by exclaiming when a new building came in view, ‘O uncle, here is one much more beautiful than any we have yet seen.’ In the meantime they were advancing into the country, and the cunning magician, who wanted to go still farther, for the purpose of putting into execution a design which he had in his head, went into one of these gardens, and sat down by the side of a large basin of pure water, which received its supply through the jaws of a bronze lion. He then pretended to be very tired, in order to give Aladdin an opportunity of resting. ‘My dear nephew,’ he said, ‘like myself, you must be fatigued. Let us rest ourselves here a little while, and get fresh strength to pursue our walk.’

“When they had seated themselves, the magician took out from a piece of linen cloth which hung from his girdle various sorts of fruits and some cakes with which he had provided himself. He spread them all out on the bank. He divided a cake between himself and Aladdin, and gave the youth leave to eat whatever fruit he liked best. While they were refreshing themselves he gave his pretended nephew much good advice, desiring him to leave off playing with boys, and to associate with intelligent and prudent men, to pay every attention to them, and to profit by their conversation. ‘You will very soon be a man yourself,’ he said, ‘and you cannot too early accustom yourself to the ways and actions of men.’ When they had finished their slight repast they rose, and pursued their way by the side of the gardens, which were separated from each other by small ditches, that served to mark the limits of each without preventing communication among them. The honesty and good understanding of the inhabitants of this city made it unnecessary that they should take any other means of guarding against injury from their neighbours. The African Magician insensibly led Aladdin far beyond the last of these gardens; and they walked on through the country till they came into the region of the mountains.

Aladdin’s mother surprised at seeing her son so handsomely dressed.

“Aladdin, who had never in his whole life before taken so long a walk, felt very much tired. ‘Where are we going, my dear uncle?’ said he; ‘we have got much farther than the gardens, and I can see nothing but hills and mountains before us. And if we go on any farther I know not whether I shall have strength enough to walk back to the city.’ ‘Take courage, nephew,’ replied his pretended uncle; ‘I wish to show you another garden that far surpasses in magnificence all you have hitherto seen. It is not much farther on, and when you get there you will readily own how sorry you would have been to have come thus near it without going on to see it.’ Aladdin was persuaded to proceed, and the magician led him on a considerable distance, amusing him all the time with entertaining stories, to beguile the way and make the distance seem less.

“At length they came to a narrow valley, situate between two mountains of nearly the same height. This was the very spot to which the magician wished to bring Aladdin, in order to put in execution the grand project that was the sole cause of his journey to China from the extremity of Africa. Presently he said to Aladdin: ‘We need go no farther. I shall here unfold to your view some extraordinary things, hitherto unknown to mortals; when you shall have seen them yon will thank me a thousand times for having made you an eye-witness of such marvels. They are indeed such wonders as no one but yourself will ever have seen. I am now going to strike a light; and do you in the meantime collect all the dry sticks and leaves that you can find, in order to make a fire.’

“So many pieces of dried sticks lay scattered about this place that Al ladin had collected more than sufficient for his purpose by the time the magician had lighted his match. He then set them on fire; and as soon as they blazed up the African threw upon them a certain perfume, which he had ready in his hand. A thick and dense smoke immediately arose, which seemed to unfold itself at some mysterious words pronounced by the magician, and which Aladdin did not in the least comprehend. A moment afterwards the ground shook slightly, and opening near the spot where they stood, discovered a square stone of about a foot and a half across, placed horizontally, with a brass ring fixed in the centre, by which it could be lifted up.

“Aladdin was dreadfully alarmed at these doings, and was about to run away, when the magician, to whom his presence was absolutely necessary in this mysterious affair, stopped him in an angry manner, at the same moment giving him a violent blow that felled him to the ground and very nearly knocked some of his teeth out, as appeared from the blood that ran from his mouth. Poor Aladdin, with tears in his eyes and trembling in every limb, got up and exclaimed, ‘What have I done to deserve so severe a blow?’ ‘I have my reasons for it,’ replied the magician. ‘I am your uncle, and consider myself as your father, therefore you should not question my proceedings. Do not, however, my boy,’ added he, in a milder tone of voice, ‘be at all afraid: I desire nothing of you but that you obey me most implicitly; and this you must do if you wish to render yourself worthy of the great advantages I mean to afford you.’ These fine speeches in some measure calmed the frightened Aladdin; and when the magician saw him less alarmed, he said: ‘You have observed what I have done by virtue of my perfumes and the words that I pronounced. I must now inform you that under the stone which you see here there is concealed a treasure, which is destined for you, and which will one day render you richer than the most powerful potentates of the earth. It is moreover true that no one in the whole world but you can be permitted to touch or lift up this stone, and go into the region that lies beneath it. Even I myself am not able to approach it and take possession of the treasure which is below it. And, in order to insure your success, you must observe and execute in every respect, even to the minutest point, the instructions I am going to give you. This is a matter of the greatest consequence both to you and myself.’

“Overwhelmed with astonishment at everything he had seen and heard, and full of the idea of this treasure which the magician said was to make him for ever happy, Aladdin forgot everything that had happened. ‘Well, my dear uncle,’ he exclaimed, as he got up, ‘what must I do? Tell me, and I am ready to obey you in everything.’ ‘I heartily rejoice, my dear boy,’ replied the magician, embracing Aladdin, ‘that you have made so good a resolution. Come to me, take hold of this ring, and lift up the stone.’ ‘I am not strong enough, uncle,’ said Aladdin; ‘you must help me.’ ‘No, no,’ answered the African Magician, ‘you have no occasion for my assistance. Neither of us will do any good if I attempt to help you; you must lift up the stone entirely by yourself. Only pronounce the name of your father and your grandfather, take hold of the ring, and lift it; it will come up without any difficulty.’ Aladdin did exactly as the magician told him; he raised the stone without any trouble, and laid it aside.

“When the stone was taken away a small excavation was visible, between three and four feet deep, at the bottom of which there appeared a small door, with steps to go down still lower. ‘You must now, my good boy,’ then said the African Magician to Aladdin, ‘observe exactly every direction I am going to give you. Go down into this cavern; and when you have come to the bottom of the steps which you see before you, you will perceive an open door, which leads into a large vaulted space divided into three successive halls. In each of these you will see on both sides of you four bronze vases, as large as tubs, full of gold and silver; but you must take particular care not to touch any of this treasure. When you get into the first hall, take up your robe and bind it closely round you. Then be sure you go on to the second without stopping, and from thence in the same manner to the third. Above everything, be very careful not to go near the walls, or even to touch them with your robe; for if any part of your dress comes in contact with them, your instant death will be the inevitable consequence. This is the reason why I have desired you to fasten your robe firmly round you. At the end of the third hall there is a door which leads to a garden, planted with beautiful trees, all of which are laden with fruit. Go straight forward, and pursue a path which you will perceive, and which will bring you to the foot of a flight of fifty steps, at the top of which there is a terrace. When you have ascended to the terrace, you will observe a niche before you, in which there is a lighted lamp. Take the lamp and extinquish it. Then throw out the wick and the liquid that is in it, and put the lamp in your bosom. When you have done this, bring it to me. Do not be afraid of staining your dress, as the liquid within the lamp is not oil; and when you have thrown it out, the lamp will dry directly. If you should feel desirous of gathering any of the fruit in the garden you may do so; there is nothing to prevent your taking as much as you please.’

“When the magician had given these directions to Aladdin, he took off a ring which he had on one of his fingers, and put it on the hand of his pretended nephew; telling him at the same time that it was a preservative against every evil that might otherwise happen to him. Again he bade him to be mindful of everything he had said to him. ‘Go, my child,’ added he, ‘descend boldly. We shall now both of us become immensely rich for the rest of our lives.’

“Aladdin gave a spring, jumped into the opening with a willing mind, and then went on down the steps. He found the three halls, which exactly answered the description the magician had given of them. He passed through them with the greatest precaution possible, as he was fearful he might perish if he did not most strictly observe all the directions he had received. He went on to the garden, and without stopping ascended to the terrace. He took the lamp which stood lighted in the niche, threw out it contents, and observing that it was, as the magician had said, quite dry, he put it into his bosom. He then came back down the terrace, and stopped in the garden to look at the fruit, which he had only seen for an instant as he passed along. The trees of this garden were all laden with the most extraordinary fruit. Each tree bore large balls, and the fruit of each tree had a separate colour. Some were white, others sparkling and transparent like crystal; some were red and of different shades; others green, blue, or violet; and some of a yellowish hue; in short, there were fruits of almost every colour. The white globes were pearls; the sparkling and transparent fruits were diamonds; the deep red were rubies; the paler a particular sort of ruby called balass; the green emeralds; the blue turquoises; the violet amethysts; those tinged with yellow sapphires; and all the other coloured fruits, varieties of precious stones; and they were all of the largest size, and the most perfect ever seen in the whole world. Aladdin, who knew neither their beauty nor their value, was not at all struck with their appearance, which did not suit his taste, as the figs, grapes, and other excellent fruits common in China would have done. As he was not yet of an age to be acquainted with the value of these stones, he thought they were only pieces of coloured glass, and did not therefore attach any importance to them. Yet the variety and contrast of so many beautiful colours, as well as the brilliancy and extraordinary size of these fruits, tempted him to gather some of each kind; and he took so many of every colour, that he filled both his pockets, as well as the two new purses that the magician had bought for him at the time he made him a present of his new dress, that everything he wore might be equally new; and as his pockets, which were already full, could not hold his two purses, he fastened them one on each side of his girdle or sash. He also wrapped some stones in its folds, as it was of silk and made very full. In this manner he carried them so that they could not fall out. He did not even neglect to fill his bosom quite full, putting many of the largest and handsomest between his robe and shirt.

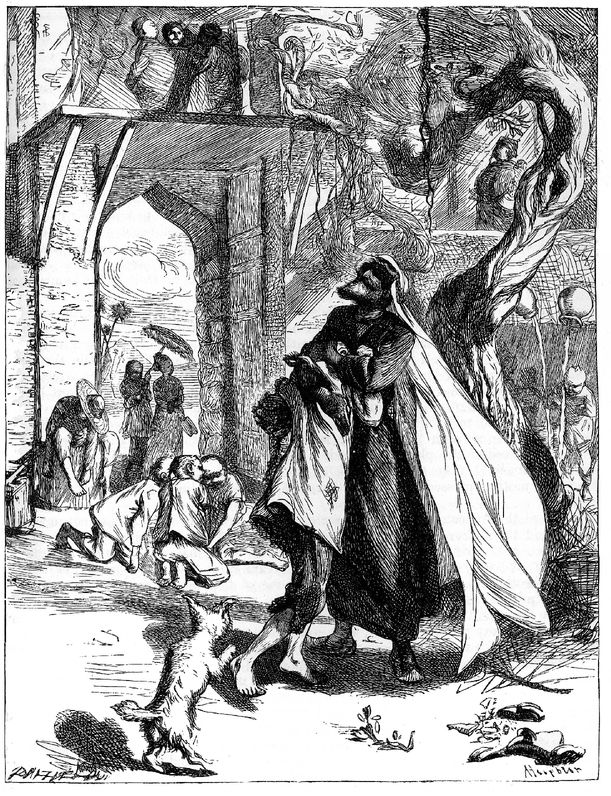

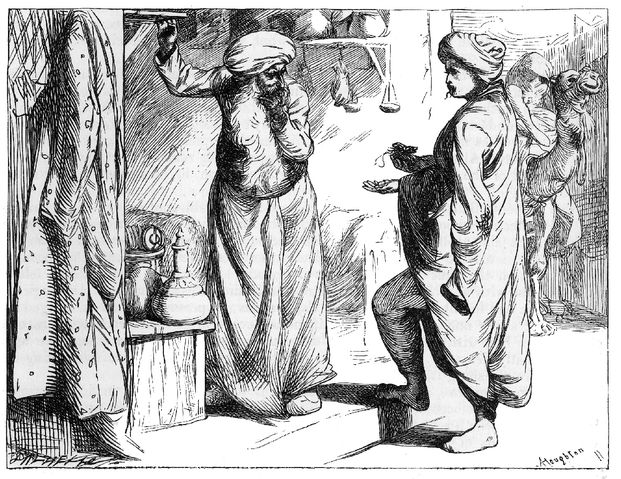

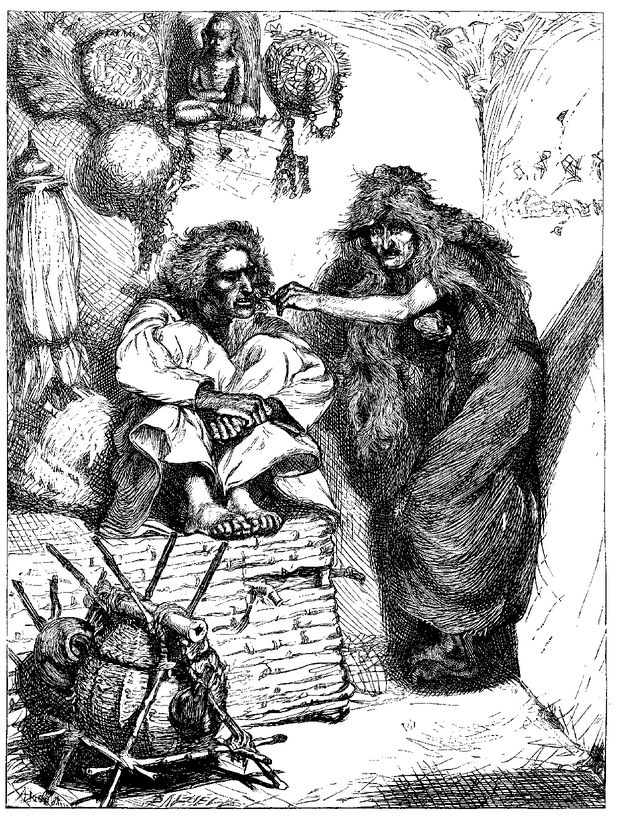

“Laden in this manner with the most immense treasure, but ignorant of its value, Aladdin made his way hastily through the three halls, that he might not make the African Magician wait too long. Having traversed them with the same caution he had used before, he began to ascend the steps he had come down, and presented himself at the entrance of the cave, where the magician was impatiently waiting for him. As soon as Aladdin perceived him he called out, ‘Give me your hand, uncle, to help me up.’ ‘My dear boy,’ replied the magician, ‘you will do better first to give me the lamp, as that will only embarrass you.’ ‘It is not at all in my way,’ said Aladdin, ‘and I will give it you when I am out of the cave.’ The magician still persisted in demanding the lamp before he helped Aladdin out of the cave; but the latter had in fact so covered it with the fruit of the trees, that he could not readily get at it, and absolutely refused to give it up till he had got out of the cave. The African Magician was then in such despair at the obstinate refusal of the boy, that at length he fell into the most violent rage. He threw a little perfume on the fire, which he had taken care to keep up; and he had hardly pronounced two magic words when the stone which served to shut up the entrance to the cavern returned of its own accord to its place, and the earth covered it exactly in the same way as when the magician and Aladdin first arrived there.

“There is no doubt that this African Magician was not the brother of Mustapha the tailor, as he had pretented to be, and consequently not the uncle of Aladdin. He was most probably a native of Africa, as that is a country where magic is more studied than in any other. He had given himself up to it from his earliest youth, and after nearly forty years spent in enchantments, experiments in geomancy, fumigations, and reading books of magic, he had at length discovered that there was in the world a certain wonderful lamp, the possession of which would make him the most powerful monarch of the universe, if he could succeed in laying hands on it. By a late experiment in geomancy he discovered that this lamp was in a subterranean cave in the middle of China, in the very spot that has just been described. Thoroughly convinced of the truth of this discovery, he had come from the farthest part of Africa, and after a long and painful journey had arrived in the city that was nearest the depository of this treasure. But though the lamp was certainly in the place which he had found out, yet he was not permitted to take it away himself, nor to go in person into the cave where it was. It was absolutely necessary that another person should go down to take it, and then put it into his hands. For this reason he had addressed himself to Aladdin, who seemed to him to be an artless youth, well adapted to perform the service he required of him; and he had resolved, as soon as he had got the lamp from the boy, to raise the last fumigation, pronounce the two magic words which produced the effect already seen, and sacrifice poor Aladdin to his avarice and wickedness, that no witness might exist who could say he was in possession of the lamp. The blow he had given Aladdin, as well as the authority he had exercised over him, were only for the purpose of accustoming the youth to fear him, and obey all his orders without hesitation, so that when Aladdin had possession of the wonderful lamp he might instantly deliver it to him. But the event disappointed his hopes and expectations, for he was in such haste to sacrifice poor Aladdin, for fear that while he was contesting the matter with him some person might come and make that public which he wished to be kept quite secret, that he completely defeated his own object.

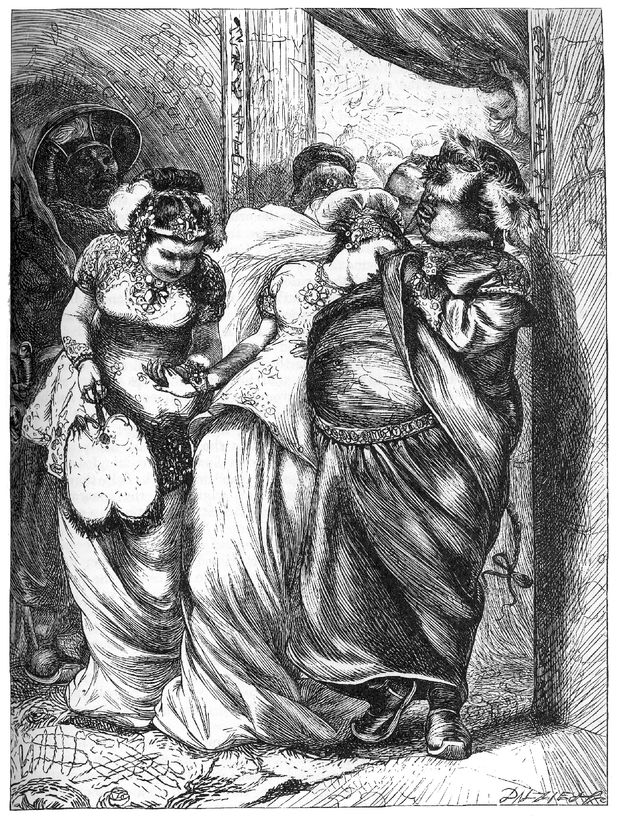

The magician commanding Aladdin to give up the lamp.

“When the magician found all his hopes and expectations for ever blasted, there remained but one thing that he could do, and that was to return to Africa; and, indeed, he set out on his journey the very same day. He was careful to travel the by-paths, in order to avoid the city where he had met Aladdin. He was also afraid to meet any person who might have seen him walk out with the lad, and come back without him.

“To judge from all these circumstances, it might naturally be supposed that Aladdin was hopelessly lost; and, indeed, the magician himself, who thought he had thus destroyed the boy, had quite forgotten the ring which he had placed on his finger, and which was now to render Aladdin the most essential service, and to save his life. Aladdin knew not the wonderful qualities either of the ring or of the lamp; and it is indeed astonishing that the loss of both these prizes did not drive the magician to absolute despair; but persons of his profession are so accustomed to defeat, and so often see their wishes thwarted, that they never cease from endeavouring to conquer every misfortune by charms, visions, and enchantments.

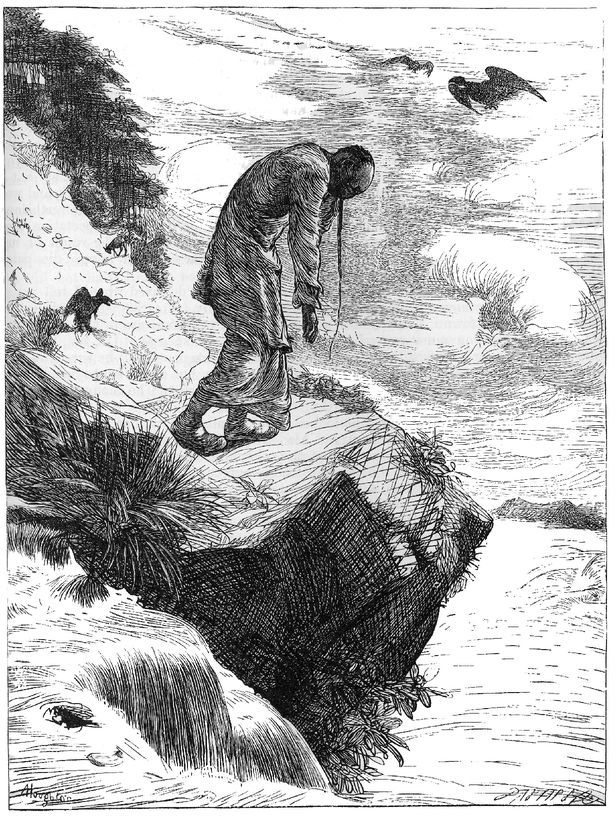

“Aladdin, who did not expect to be thus wickedly deceived by his pretended uncle, after all the kindness and generosity which the latter had shown to him, was in the highest degree astonished at his position. When he found himself thus buried alive, he called aloud a thousand times to his uncle, telling him he was ready to give up the lamp. But all his cries were useless, and having no other means of making himself heard, he remained in perfect darkness, bemoaning his unhappy fate. His tears being at length exhausted, he went down to the bottom of the flight of stairs, intending to go towards the light in the garden where he had before been. But the walls, which had been opened by enchantment, were now shut by the same means. He groped along the walls to the right and left several times, but could not discover the smallest opening. He then renewed his cries and tears, and sat down upon the steps of his dungeon, without the least hope that he should ever again see the light of day, and with the melancholy conviction that he should only pass from the darkness he was now in to the shades of an inevitable and speedy death.

“Aladdin remained two days in this hopeless state, without either eating or drinking. On the third day, regarding his death as certain, he lifted up his hands, and joining them as in the act of prayer, he wholly resigned himself to the will of Heaven, and uttered in a loud tone of voice: ‘There is no strength or power but in the high and great Allah.’ In this action of joining his hands he happened, quite unconsciously, to rub the ring which the African Magician had put upon his finger, and of the virtue of which he was as yet ignorant. When the ring was thus rubbed, a genie of enormous stature and a most horrid countenance instantly rose as it were out of the earth before him. This genie was so tall that his head touched the vaulted roof, and he addressed these words to Aladdin: ‘What dost thou command? I am ready to obey thee as thy slave—as the slave of him who has the ring on his finger—both I and the other slaves of the ring.’

“At any other moment, and on any other occasion, Aladdin, who was totally unaccustomed to such apparitions, would have been so frightened at the sight of this startling figure that he would have been unable to speak; but he was so entirely taken up with the danger and peril of his situation, that he answered without the least hesitation, ‘Whoever you are, take me if you can out of this place.’ He had scarcely pronounced these words when the earth opened, and he found himself outside the cave, at the very spot to which the magician had brought him. It will easily be understood that, after having remained in complete darkness for so long a time, Aladdin had at first some difficulty in supporting the brightness of open day. By degrees, however, his eyes became accustomed to the light; and on looking round him he was surprised to find not the smallest opening in the earth. He could not comprehend in what manner he had so suddenly emerged from it. But he could recognise the place where the fire had been made, which he recollected was close to the entrance into the cave. Looking round towards the city, he descried it in the distance, surrounded by the gardens, and thus he knew the road he had come with the magician. He returned the same way, thanking Heaven for having again suffered him to behold and revisit the face of the earth, which he had quite despaired of ever seeing more. He arrived at the city, but it was only with great difficulty that he got home. When he was within the door, the joy he experienced at again seeing his mother, added to the weak state he was in from not having eaten anything for the space of three days, made him faint, and it was some time before he came to himself. His mother, who had already mourned for him as lost or dead, seeing him in this state, used every possible effort to restore him to life. At length he recovered, and the first thing he said to his mother was, ‘O my dear mother, bring me something to eat before you do anything else. I have tasted nothing these three days.’ His mother instantly set what she had before him. ‘My dear child,’ said she as she did so, ‘do not hurry yourself, for that is dangerous. Eat but little, and that slowly; and you must take great care what you do in your exhausted state. Do not even speak to me. When you have regained your strength you will have plenty of time to relate to me everything that has happened to you. I am full of joy at seeing you once more, after all the grief I have suffered since Friday, and all the trouble I have also taken to learn what was become of you, when I found that night came on and you did not return home.’

“Aladdin followed his mother’s advice. He ate slowly and sparingly, and drank with equal moderation. When he had done he said: ‘I have great reason, my dear mother, to complain of you for putting me in the power of a man whose object was to destroy me, and who at this very moment supposes my death so certain that he cannot doubt either that I am no longer alive, or at least that I shall not survive another day. But you took him to be my uncle, and I was also equally deceived. Indeed, how could we suspect him of any treachery, when he almost overwhelmed me with his kindness and generosity, and made me so many promises of future advantage? But I must tell you, mother, that he was a traitor, a wicked man, a cheat. He was so good and kind to me only that, after answering his own purpose, he might destroy me, as I have already told you, and neither you nor I would ever have been able to know the reason. For my part, I can assure you I have not given him the least cause for the bad treatment I have received; and you will yourself be convinced of this from the faithful and true account I am going to give you of everything that has happened from the moment when I left you till he put his wicked design in execution.’

‘Aladdin then related to his mother all that had happened to him and the magician on the day when the latter came and took him away to see the palaces and gardens round the city. He told of what had befallen him on the road and at the place between the two mountains, where the magician worked such wonders; how, by throwing the perfume into the fire and pronouncing some magical words, he had caused the earth instantly to open, and discovered the entrance into a cave that contained inestimable treasures. He did not forget to mention the blow that the magician had given him, and the manner in which this man, after having first coaxed him, had persuaded him by means of the greatest promises, and by putting a ring upon his finger, to descend into the cave. He omitted no circumstance that had happened, and told all he had seen in going backwards and forwards through the three halls, in the garden, or on the terrace whence he had taken the wonderful lamp. He took the lamp itself out of his bosom and showed it to his mother, as well as the transparent and different coloured fruits that he had gathered as he returned through the garden. He gave the two purses that contained these fruits to his mother, who did not set much value upon them. The fruits were, in fact, precious stones; and the lustre which they threw around them by means of a lamp that hung in the chamber, and which almost equalled the radiance of the sun, ought to have shown her they were of the greatest value; but the mother of Aladdin knew no more of their value than her son. She had been brought up in comparative poverty, and her husband had never been rich enough to bestow any jewels upon her. Besides, she had never even seen any such treasures among her relations or neighbours; and therefore it was not at all surprising that she considerd them as things of no value—mere playthings to please the eye by the variety of their colours. Aladdin therefore put them all behind one of the cushions of the sofa on which they were sitting.

“He finished the recital of his adventures by telling his mother how, when he came back and presented himself at the mouth of the cave and refused to give the lamp to the magician, the entrance of the cave was instantly closed by means of the perfume that the magician threw on the fire and by some words that he pronounced. He could not refrain from tears when he represented the miserable state he found himself in, as it were buried alive in that fatal cave, till the moment he obtained his freedom and emerged into the upper air by means of the ring, of which he did not even now know the virtues. When he had finished his story, he said to his mother: ‘I need not tell you more, for you know the rest. This is a true account of my adventures and of the dangers I have been in since I left you.’

“Wonderful and amazing as this relation was, distressing too as it must have been for a mother who tenderly loved her son in spite of his defects, the widow had the patience to hear it to the end without once interrupting him. At the most affecting parts, however, particularly those that revealed the wicked intentions of the African Magician, she could not help showing by her gestures how much she detested him, and how much he excited her indignation. But Aladdin had no sooner concluded than she began to abuse the pretended uncle in the strongest terms. She called him a traitor, a barbarian, a cheat, an assassin, a magician, the enemy and de stroyer of the human race. ‘Yes, my child,’ she cried, ‘he is a magician; and magicians are public evils! They hold communication with demons by means of their sorceries and enchantments. Blessed be Heaven that has not suffered the wickedness of this wretch to have its full effect upon you! You, too, ought to return thanks for your deliverance. Your death would have been inevitable if Heaven had not come to your assistance, and if you had not implored its aid.’ She added many more words of the same sort, showing also her complete detestation of the treachery with which the magician had treated her son; but as she was exclaiming in this manner, she perceived that Aladdin, who had not slept for three days, wanted rest. She made him, therefore, retire to bed, and soon afterwards went herself.

“As Aladdin had not been able to take any repose in the subterraneous place in which he had been as it were buried with the prospect of certain destruction, it is no wonder that he passed the whole of that night in the most profound sleep, and that it was even late the next morning before he awoke. He at last rose, and the first thing he said to his mother was, that he was very hungry, and that she could not oblige him more than by giving him something for breakfast. ‘Alas! my child,’ replied his mother, ‘I have not a morsel of bread to give you. Last night you finished all the trifling store of food there was in the house. But have a little patience, and it shall not be long before I will bring you some. I have here a little cotton I have spun; I will go and sell it, and purchase something for our dinner.’ ‘Keep your cotton, mother,’ said Aladdin, ‘for another time, and give me the lamp which I brought with me yesterday. I will go and sell that; and the money it will bring will serve us for breakfast and dinner too—may, perhaps also for supper.’

“Aladdin’s mother took the lamp from the place where she had deposited it. ‘Here it is,’ she said to her son; ‘but it seems to me to be very dirty. If I were to clean it a little perhaps it might sell for something more.’ She then took some water and a little fine sand to clean the lamp, but she had scarcely begun to rub it, when instantly, and in the presence of her son, a hideous and gigantic genie rose out of the ground before her, and cried with a voice as loud as thunder: ‘What are thy commands? I am ready to obey thee as thy slave, and the slave of those who have the lamp in their hands; both I and the other slaves of the lamp!’ The mother of Aladdin was too much startled to answer this address. She was unable to endure the sight of an apparition so hideous and alarming; and her fears were so great, that as soon as the genie began to speak she fell down in a fainting-fit.

“Aladdin had once before seen a similar appearance in the cavern. He did not lose either his presence of mind or his judgment; but he instantly seized the lamp, and supplied his mother’s place, by answering for her in a firm tone of voice: ‘I am hungry; bring me something to eat.’ The genie disappeared, and returned a moment after with a large silver basin, which he carried on his head, and twelve covered dishes of the same material filled with the choicest meats properly arranged, and six loaves as white as snow upon as many plates. He carried two bottles of the most excellent wine and two silver cups in his hands. He placed all these things upon the sofa, and instantly vanished.

“All this had occurred in so short a time, that Aladdin’s mother had not recovered from her fainting-fit before the genie had disappeared the second time. Aladdin, who had before thrown some water over her without any effect, was about to renew his endeavours, but at the very instant, whether her fluttered spirits returned of themselves, or that the smell of the dishes which the genie had brought had a reanimating effect, she quite recovered. ‘My dear mother,’ cried Aladdin, ‘there is nothing the matter. Come and eat; here is something that will put you in good spirits again, and at the same time satisfy my hunger. Come, do not let us suffer these good things to get cold before we begin.’

“His mother was extremely astonished when she beheld the large basin, the twelve dishes, the six loaves, the two bottles of wine and two cups, and perceived the delicious odour that exhaled from them. ‘O my child!’ she cried, ‘how came all this abundance here? And whom have we to thank for such liberality? The sultan surely cannot have been made acquainted with our poverty, and have had compassion upon us?’ ‘My good mother,’ replied Aladdin, ‘come and sit down, and begin to eat; you are as much in want of food as I am. I will tell you everything when we have broken our fast.’ They then sat down, and both of them ate with the greater appetite, as neither mother nor son had ever seen a table so well supplied.

“During the repast the mother of Aladdin could not help stopping frequently to look at and admire the basin and dishes, although she was not quite sure whether they were silver or any other metal, so little was she accustomed to things of this sort. In fact, she did not regard their value, of which she was ignorant; it was only the novelty of their appearance that attracted her admiration. Nor, indeed, was her son better informed on the subject than herself. Although they both merely intended to make a simple breakfast, yet they sat so long that the dinner-hour came before they had risen. The dishes were so excellent they almost increased their appetites; and, as the viands were still hot, they thought it no bad plan to join the two meals together; and therefore they dined before they got up from breakfast. When they had made an end of their double repast, they found that enough remained, not only for supper, but even for two meals the next day as plentiful as those they had just made.

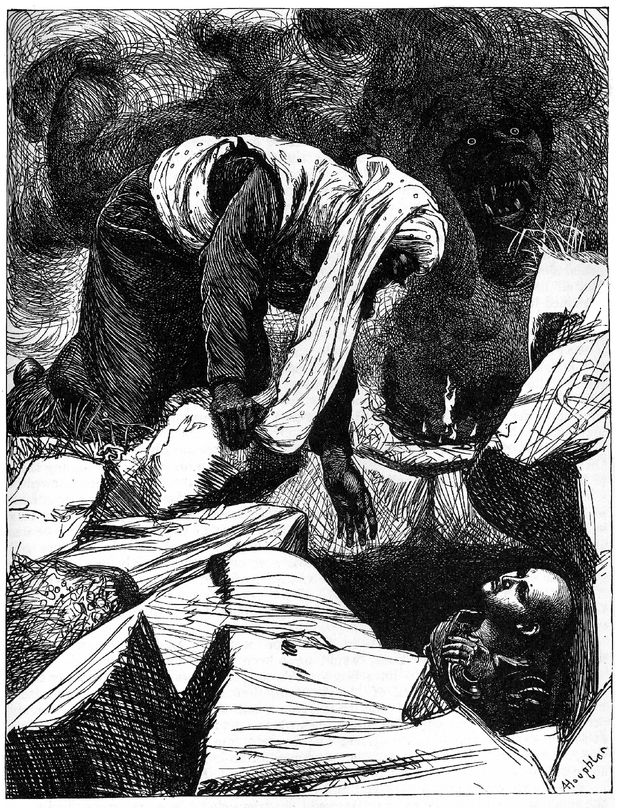

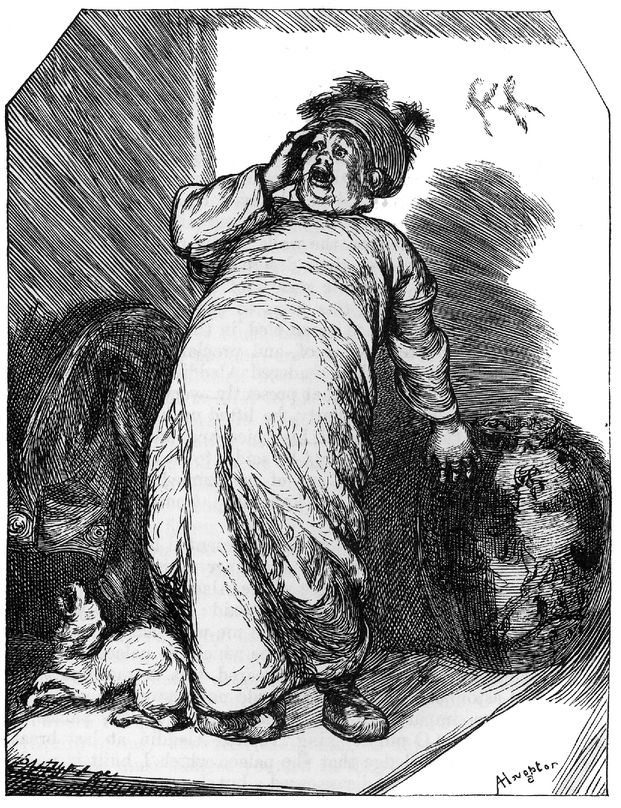

“Ah, my son, take the lamp out of my sight!”

“When Aladdin’s mother had taken away the things, and put aside what they had not consumed, she came and seated herself on the sofa near her son. ‘I now expect, my dear son,’ she said, ‘that you will satisfy my impatient curiosity, and let me hear the account you have promised me.’ Aladdin then related to his mother everything that had passed between him and the genie from the time when she fainted with fear till she again came to herself. At this discourse of her son, and his account of the appearance of the genie, Aladdin’s mother was in the greatest astonishment. ‘What is this you tell me, child, about your genie?’ she exclaimed. ‘Never since I was born have I heard of any person of my acquaintance who has seen one. How comes it, then, that this villanous genie should have accosted me? Why did he not rather address himself to you, to whom he had before appeared in the subterraneous cavern?’

“ ‘Mother,’ replied Aladdin, ‘the genie who appeared just now to you is not the same who appeared to me. In some things, indeed, they resemble each other, being both as large as giants; but they are very different both in their countenance and dress, and they belong to different masters. If you recollect, he whom I saw called himself the slave of the ring which I had on my finger; and the genie who appeared to you was the slave of the lamp you had in your hand; but I believe you did not hear him, as you seemed to faint the instant he began to speak.’ ‘What!’ cried his mother, ‘was your lamp the reason why this cursed genie addressed himself to me rather than to you? Ah, my son, take the lamp out of my sight, and put it were you please, so that I never touch it again. Indeed, I would rather that you should throw it away or sell it than run the risk of being killed with fright by again touching it. And if you will follow my advice, you will put away the ring as well. We ought to have no commerce with genii; they are demons, and our Prophet has told us to beware of them.’

“ ‘With your permission, however, my dear mother,’ replied Aladdin, ‘I shall beware of parting with this lamp, which has already been so useful to us both. I have, indeed, once been very near selling it. Do you not see what it has procured us, and that it will also continue to furnish us with enough for our support? You may easily judge, as I do, that it was not for nothing my wicked pretended uncle gave himself so much trouble and undertook so long and fatiguing a journey. He did all this merely to get possession of this wonderful lamp, which he preferred to all the gold and silver which he knew was in the three halls, and which I myself saw, as he had before told me I should. He knew too well the worth and qualities of this lamp to wish for anything else from that immense treasure. And since chance has discovered its virtues to us, let us avail ourselves of them; but we must be careful not to make any parade, lest we draw upon ourselves the envy and jealousy of our neighbours. I will take the lamp out of your sight, and put it where I shall be able to find it whenever I have occasion for it, since you are so much alarmed at the appearance of genii. Again, I cannot make up my mind to throw the ring away. But for this ring you would never have seen me again; and even if I had been alive now, I should have had but a short time to live. You must permit me, therefore, to keep and to wear it always very carefully on my finger. Who can tell if some danger may not again happen to me which neither you nor I can now foresee, and from which the ring may deliver me?’ As the arguments of Aladdin appeared very just and reasonable, his mother had no further objections to make. ‘Do as you like, my son,’ she cried. ‘As for me, I wish to have nothing at all to do with genii; and I declare to you that I entirely wash my hands of them, and will never even speak of them again.’

“At supper the next evening, the remainder of the provisions the genie had brought was consumed. The following morning, Aladdin, who did not like to wait till hunger pressed him, took one of the silver plates under his robe, and went out early in order to sell it. He addressed himself to a Jew whom he happened to meet. Aladdin took him aside, and showing him the plate, asked if he would buy it.

“The Jew, a clever and cunning man, took the plate and examined it. Directly he had satisfied himself that it was good silver, he desired to know how much the seller expected for it. Aladdin, who knew not its value, and who had never had any dealings of the sort before, merely said that he supposed the Jew knew what the plate was worth, and that he would depend upon the purchaser’s honour. Uncertain whether Aladdin was acquainted with its real value or not, the Jew took out of his purse a piece of gold, which was exactly one seventy-second part of the value of the plate, and offered it to Aladdin. The latter eagerly took the money, and without staying to say anything more, went away so quickly that the Jew, not satisfied with the exorbitant profit he had made by his bargain, was very sorry he had not foreseen Aladdin’s ignorance of the value of the plate, and in consequence offered him much less for it. He was almost ready to run after the young man to get something back from him out of the piece of gold he had given him. But Aladdin himself ran very fast, and was already so far away that the Jew would have found it impossible to overtake him.

“On his way home, Aladdin stopped at a baker’s shop, where he bought enough bread for his mother and himself, paying for his purchase out of his piece of gold, and receiving the change. When he came home he gave the rest of the money to his mother, who went to the market and purchased as much provision as would last them for several days.

“They thus continued to live quietly and economically till Aladdin had sold all the twelve dishes, one after the other, to the same Jew, exactly as he had sold the first; and then they found they wanted more money. The Jew, who had given Aladdin a piece of gold for the first, dared not offer him less for the other dishes, for fear he might lose so good a customer; he therefore bought them all at the same rate. When the money for the last plate was expended, Aladdin had recourse to the basin, which was at least ten times as heavy as any of the plates. He wished to carry this to his merchant, but its great weight prevented him; he was obliged, therefore, to seek out the Jew, and bring him to his mother’s. After ascertaining the weight of the basin, the Jew counted out ten pieces of gold, with which Aladdin was satisfied.

“While these ten pieces lasted they were devoted to the daily expenses of the house. In the meantime Aladdin, though accustomed to lead an idle life, abstained from going to play with other boys of his own age from the time of his adventure with the African Magician. He now spent his days in walking about, or conversing with men whose acquaintance he made. Sometimes he stopped in the shops belonging to wealthy merchants, where he listened to the conversation of the people of distinction and education who came there, and who made these shops a sort of meeting-place. The information he thus obtained gave him a slight knowledge of the world.

“When his ten pieces of gold were spent Aladdin had recourse to the lamp. He took it up and looked for the particular spot that his mother had rubbed. As he easily perceived the place where the sand had touched the lamp, he applied his hand to the same spot, and the genie whom he had before seen instantly appeared. But as Aladdin had rubbed the lamp more gently than his mother had done, the genie spoke to him also in a softened tone. ‘What are thy commands,’ said he, in the same words as before; ‘I am ready to obey thee as thy slave, and the slave of those who have the lamp in their hands, both I, and the other slaves of the lamp.’ ‘I am hungry,’ cried Aladdin: ‘bring me something to eat.’ The genie disappeared, and in a short time returned, loaded with a service similar to that which he had brought before. He placed it upon the sofa, and vanished in an instant.

“As Aladdin’s mother was aware of the intention of her son when he took the lamp, she had gone out on some business, that she might not even be in the house when the genie should make his appearance. She soon afterwards came in, and saw the table and sideboard handsomely furnished; nor was she less surprised at the effect of the lamp this time than she had been before. Aladdin and his mother immediately took their seats at the table, and after they had finished their repast there still remained sufficient food to last them two whole days.

“When Aladdin again found that all his provisions were gone, and he had no money to purchase any, he took one of the silver dishes, and went to look for the Jew who had bought the former dishes of him, intending to deal with him again. As he walked along he happened to pass the shop of a goldsmith, a respectable old man, whose probity and general honesty were unimpeachable. The goldsmith, who perceived him, called to him to come into the shop. ‘My son,’ said he, ‘I have often seen you pass this way, loaded as you are now, and each time you have spoken to a certain Jew; and then I have seen you come back again empty-handed. It has struck me that you went and sold him what you carried. But perhaps you do not know that this Jew is a very great cheat; nay, that he will even deceive his own brethren, and that no one who knows him will have any dealings with him? Now, I have merely a proposition to make to you, and then you can act exactly as you like in the matter. If you will show me what you are now carrying, and if you are going to sell it, I will faithfully give you what it is worth, if it be anything in my way of business; if not, I will introduce you to other merchants who will deal honestly with you.’

“The hope of getting a better price for his silver plate induced Aladdin to take it out from under his robe, and show it to the goldsmith. The old man, who knew at first sight that the plate was of the finest silver, asked him if he had sold any like this to the Jew, and if so, how much he had received for them. Aladdin plainly told him that he had sold twelve, and that the Jew had given him a piece of gold for each. ‘Out upon the thief!’ cried the merchant. ‘However, my son, what is done cannot be undone, and let us think of it no more; but I will let you see what your dish, which is made of the finest silver we ever use in our shops, is really worth, and then you will understand to what extent the Jew has cheated you.’

“The goldsmith took his scales, weighed the dish, and after explaining to Aladdin how much a mark of silver was, what it was worth, and how it was divided, he made him observe that, valued according to weight, the plate was worth seventy-two pieces of gold, which he immediately counted out to him. ‘This,’ said he, ‘is the exact value of your plate; if you doubt what I say, you may go to any of our goldsmiths, and if you find that he will give you more for it, I promise to forfeit double the sum. We make our profit by the fashion or workmanship of the goods we buy in this manner; and with this even the most equitable Jews are not content.’ Aladdin thanked the goldsmith for the good and profitable advice he had given him; and for the future he carried his dishes to no one else. He took the basin also to this goldsmith’s shop, and received the value according to its weight.

“Although Aladdin and his mother had an inexhaustible source of money in their lamp, and could procure what they wished whenever they wanted anything, they continued to live with the same frugality they had always shown, except that Aladdin devoted a small sum to innocent amusements, and to procuring some things that were necessary in the house. His mother provided her own dress, paying for it with the price of the cotton she spun. As they lived thus quietly, it is easy to conjecture how long the money arising from the sale of the twelve dishes and the basin must have lasted them. Thus mother and son lived very happily together for many years, with the profitable assistance which Aladdin occasionally procured from the lamp.

“During this interval Aladdin resorted frequently to those places where persons of distinction were to be met with. He visited the shops of the most considerable merchants in gold and silver stuffs, in silks, fine linens, and jewellery; and, by sometimes taking part in their conversation, he insensibly acquired the style and manners of good company. By frequenting the jewellers’ shops he learned how erroneous was the idea he had formed that the transparent fruits he had gathered in the garden whence he took the lamp were only coloured glass: he now knew their value, for he was convinced that they were jewels of inestimable price. He had acquired this knowledge by observing all kinds of precious stones that were bought and sold in the shops; and as he did not see any stones that could be compared with those he possessed, either in brilliancy or in size, he concluded that, instead of being the possessor of some bits of common glass which he had considered as trifles of little worth, he had really procured a most invaluable treasure. He had, however, the prudence not to mention this discovery to any one, not even to his mother; and doubtless it was in consequence of his silence that he afterwards rose to the great good fortune to which we shall in the end see him elevated.

“One day as he was walking abroad in the city, Aladdin heard the criers reading a proclamation of the sultan, ordering all persons to shut up their shops, and retire into their houses, until the Princess Badroulboudour,

w the daughter of the sultan, had passed by on her way to the bath, and had returned to the palace.

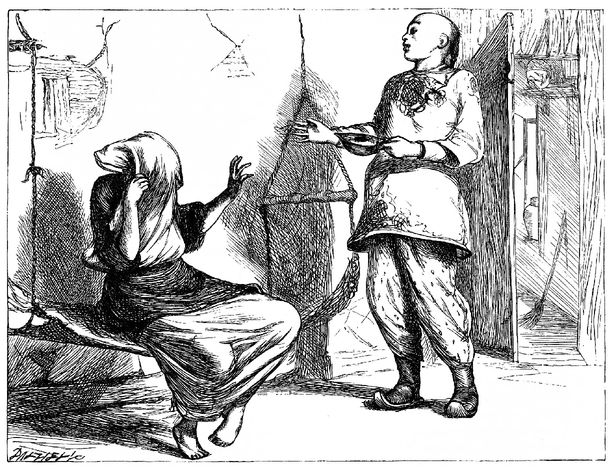

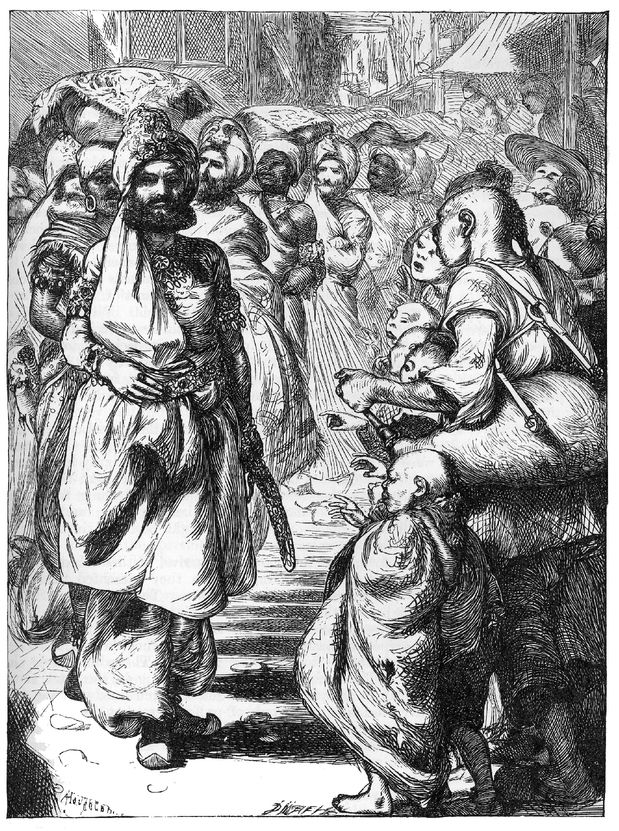

Aladdin sees the Princess Badroulboudour on her way to the bath.

“The casual hearing of this order created in Aladdin a curiosity to see the princess unveiled; but this he could only accomplish by going to some house whose inmates he knew, and by looking through the lattices. This plan, however, by no means satisfied him, because the princess usually wore a veil as she went to the bath. He thought at last of a scheme, which, on being tried, proved completely successful. He went and hid himself behind the door of the bath, which was so constructed that he could not fail to see the face of every one who passed through it.

“Aladdin had not waited long in his place of concealment before the princess made her appearance; and he saw her perfectly well through a crevice, without being himself seen. The princess was accompanied by a great crowd of women and eunuchs, who walked on either side of her, while others followed her. When she had come within three or four paces of the door of the bath, she lifted up the veil which not only concealed her face but encumbered her movements, and thus gave Aladdin an opportunity of seeing her quite at his ease as she approached the door.

“Till this moment Aladdin had never seen any woman without her veil, except his mother, who was rather old, and who, even in her youth, had not possessed any beauty. He was therefore incapable of forming any judgment respecting the attractions of women. He had indeed heard that there were some ladies who were surprisingly beautiful, but the mere description of beauty in words never makes the same impression which the sight of beauty itself affords.

“The appearance of the Princess Badroulboudour dispelled the notion Aladdin had entertained that all women resembled his mother. His opinions underwent an entire change, and his heart could not help surrendering itself to the object whose appearance had captivated him. The princess was, in fact, the most beautiful brunette ever seen. Her eyes were large, well shaped, and full of fire; yet the expression of her countenance was sweet and modest. Her nose was pretty and properly proportioned; her mouth small; her lips were like vermillion, and beautifully formed; in short, every feature of her face was perfectly lovely and regular. It is, therefore, by no means wonderful that Aladdin was dazzled and almost bereft of his senses at beholding a combination of charms to which he had hitherto been a stranger. Besides all these perfections, this princess had an elegant figure and a most majestic air, and her appearance at once enforced the respect that was due to her rank.

“Long after she had passed him and entered the bath, Aladdin stood still like a man entranced, retracing and impressing more strongly on his own mind the image by which he had been charmed, and which had penetrated to the very bottom of his heart. At last he came to himself; and recollecting that the princess was gone, and that it would be perfectly useless for him to linger in the hope of seeing her come out, as her back would then be towards him and she would also be veiled, he determined to quit his post and retire.

“When he came home Aladdin was unable to conceal his disquietude and distress from the observation of his mother. She was very much surprised to see him appear so melancholy, and to notice the embarrassment of his manner. She asked him if anything had happened to him, or if he were unwell. He gave her no answer whatever, but continued sitting on the sofa with an air of abstraction for a long time, entirely taken up in retracing in his imagination the lovely image of the Princess Badroulboudour. His mother, who was employed in preparing supper, forbore to trouble him. As soon as the meal was ready she served it up close to him on the sofa, and sat down to table. But as she perceived that Aladdin paid no attention to what went on around him, she invited him to eat; but it was only with great difficulty she could get him to change his position. He at length began to eat, but in a much more sparing manner than usual. He sat with his eyes cast down, and kept such a profound silence that his mother could not get a single word from him in answer to all the questions she put to him in her anxiety to learn the cause of so extraordinary a change.

“After supper she wished to renew the subject, and inquire the cause of Aladdin’s great melancholy; but she could not get him to give her an answer, and he determined to go to bed to escape the questions with which she plied him.

“Aladdin passed a wakeful night, occupied by thoughts of the beauty and charms of the Princess Badroulboudour; but the next morning, as he was sitting upon the sofa opposite his mother, who was spinning her cotton as usual, he addressed her in the following words: ‘O my mother, I will now break the long silence I have kept since my return from the city yesterday morning, for I think, nay, indeed, I have perceived, that it has pained you. I was not ill, as you seemed to think, nor is anything the matter with me now; yet I can assure you that the pain I at this moment feel, and which I shall ever continue to feel, is much worse than any disease. I am myself ignorant of the nature of my feelings, but I have no doubt that when I have explained myself you will understand them.

“ ‘It was not proclaimed in this quarter of the city,’ continued Aladdin, ‘and therefore you of course have not heard that the Princess Badroulboudour, the daughter of our sultan, went to the bath after dinner yesterday: I learnt this intelligence during my morning walk in the city. An order was consequently published that all the shops should be shut up, and every one should keep at home, that the honour and respect which is due to the princess might be paid to her, and that the streets through which she had to pass might be quite clear. As I was not far from the bath at the time, the desire I felt to see the face of the princess made me take it into my head to place myself behind the door of the bath, supposing, as indeed it happened, that she might take off her veil just before she went into the building. You recollect the situation of that door, and can therefore very well imagine that I could easily obtain a full sight of her, if what I conjectured should actually take place. She did take off her veil as she passed in, and I had the supreme happiness and satisfaction of seeing this beautiful princess. This, my dear mother, is the true cause of the state you saw me in yesterday, and the reason of the silence I have hitherto kept. I feel such a violent affection for this princess, that I know no terms strong enough to express it; and as my ardent love for her increases every instant, I am convinced it can only be satisfied by the possession of the amiable Princess Badroulboudour, whom I have resolved to ask in marriage of the sultan.’

“Aladdin’s mother listened with great attention to this speech of her son’s till he came to the last sentence; but when she heard that it was his intention to demand the Princess Badroulboudour in marriage, she could not help bursting out into a violent fit of laughter. Aladdin wished to speak again, but she prevented him. ‘Alas! my son, she cried, ‘what are you thinking of? You must surely have lost your senses to talk thus.’ ‘Dear mother,’ replied Aladdin, ‘I do assure you I have not lost my senses—I am in my right mind. I foresaw very well that you would reproach me with folly and madness, even more than you have done; but whatever you may say, nothing will prevent me from again declaring to you that my resolution to demand the Princess Badroulboudour of the sultan, her father, in marriage, is absolutely fixed and unchangeable.’

“ ‘In truth, my son,’ replied his mother, very seriously, ‘I cannot help telling you that you seem entirely to have forgotten who you are; and even if you are determined to put this resolution in practice, I do not know who will have the audacity to carry your message to the sultan.’ ‘You yourself must do that,’ answered he instantly, without the least hesitation. ‘I!’ cried his mother, with the strongest marks of surprise, ‘I go to the sultan!—not I indeed. Nothing shall induce me to engage in such an enterprise. And pray, my son, whom do you suppose you are,’ she continued, ‘that you have the impudence to aspire to the daughter of the sultan? Have you forgotten that you are the son of one of the poorest tailors in this city, and that your mother’s family cannot boast of any higher origin? Do you not know that sultans do not deign to bestow their daughters even upon the sons of other sultans, unless the suitors have some chance of succeeding to the throne?’

“My dear mother,’ replied Aladdin, ‘I have already told you that I perfectly foresaw all the objections you have made, and am aware of everything that you can add more; but neither your reasons nor remonstrances will in the least change my resolution. I have told you that I would demand the Princess Badroulboudour in marriage, and that you must impart my wish to the sultan. It is a favour which I entreat at your hands with all the respect I owe to you, and I beg you not to refuse me, unless you would see me die, whereas by granting it you will give me life, as it were, a second time.’

“Aladdin’s mother was very much embarrassed when she saw with what obstinacy her son persisted in his mad design. ‘My dear son,’ she said, ‘I am your mother, and like a good mother who has brought you into the world, I am ready to do anything that is reasonable and suited to your situation in life and my own, and to undertake anything for your sake. If this business were merely to ask in marriage the daughter of any of our neighbours whose condition was similar to yours, I would not object, but would willingly employ all my abilities in your cause. But to hope for success, even with the daughter of one of our neighbours, you ought to possess some little fortune, or at least to be master of some business. When poor people like us wish to marry, the first thing we ought to think about is how to make a livelihood. But you, regardless of the lowness of your birth, and of your want of merit or fortune, at once aspire to the highest prize, and pretend to nothing less than to ask in marriage the daughter of your sovereign, who has but to open his lips to blast all your designs and destroy you at once.